Munin

VIP Member

- Dec 5, 2008

- 1,308

- 96

- 83

World War II: the forgotten fight against Vichy France - Catholic Herald OnlineWorld War II: the forgotten fight against Vichy France

John Hinton finds that the French did fight tenaciously in World War II – for the Nazis

16 October 2009

England's Last War Against France: Fighting Vichy

By Colin Smith

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25

It played out exactly to a sombre deadline: a steaming hot day early in July 1940 when Royal Navy battleships loomed over the horizon near the port of Mers-El-Kibar in French Algeria, opened fire and destroyed a large part of the French fleet, killing 1,300 of its sailors within 10 minutes. The British Admiral, Sir James Somerville, had negotiated for hours, trying to persuade the French to elope with the Royal Navy and join the fight against the Axis. He didn't like it but warned his opposite number: "If you refuse these fair offers, I must with profound regret sink your ships."

The French sailors had dreamed of chasing German raiders with their British colleagues. But their admiral, puffed-up and indecisive, refused. And now their dreams - and their lives - were lost as the British salvoes crashed among them.

Gone, too, was the entente cordiale. France had already surrendered after an unequal fight against the Panzers and 100,000 of its soldiers had joined the British Army's evacuation from the beaches of Dunkirk. Astonished by his rapid victory, Hitler had generously pledged that France keep its fleet, as long as it remained neutral.

Clearly, then, the broadsides between sailing ships and the charges of Napoleonic cavalry were not the last time England took up arms against France. This second outbreak of hostilities was a complex and ugly period within living memory which many Frenchmen would very much like to forget.

At the heart of this "forgotten" war, brought to life in Colin Smith's vivid new account, was the old hero of Verdun, Marshal Philippe Pétain. He had sensed France could never win against the military might of Hitler's Germany and couldn't bear a repeat of the First World War's toll of a million French dead. And after France's military defeat and the subsequent rescue of Allied forces from the beaches of Dunkirk he remained sure his judgment was correct.

With no choice in the matter, he agreed to the German occupation of the country from northern France to a bulge below Paris. South of this line, France would be independently governed by him and his staff from the spa town of Vichy. To the Resistance fighters and their leader, Charles de Gaulle, safe for the time being in London, the arrangement was a sell-out.

Ever a pragmatist, Winston Churchill was less interested in the antics of the Resistance movement than the strategic importance of the French fleet and the danger from its colonial troops if they turned over to the Nazi cause. Something had to be done, since the fleet could be requisitioned by the Germans and used in an invasion of the poorly-defended British Isles. So he ordered the sinking - at which news MPs in the House of Commons cheered and threw their order papers in the air.

Yet Churchill's order was to forever turn many Frenchmen against England, including the ostensibly neutral military forces in what was now Vichy France. Many of them would now be happy to collaborate with the Germans against "perfidious Albion".

Until at least the winter of 1942, Vichy forces abroad fought the allies with a vigour that caused the Prime Minister to remark that he wished they had tried as hard against the Germans in 1940. There were a number of tough campaigns and Smith, a veteran war correspondent, has ably drawn them together for the first time into a continuous fast-paced narrative; many passages are as replete with action as a smoking gun.

The French had administered Syria since 1918. In June 1941 Churchill reluctantly committed forces to occupy the country when Germans arrived there, and Vichy aircraft began escorting Luftwaffe operations that threatened British control of Iraq.

Contemporary accounts maintain that Vichy handled captured Allied servicemen and civilian internees with brutality. "The French were rotten," said a survivor from the sunken liner Laconia held in Morocco. "We ended up thinking of them as our enemies, and not the Germans."

British and Commonwealth soldiers died under Vichy guns in Syria, even as the Allies were struggling to hold off Rommel in the desert. The novelist Roald Dahl, who flew Hurricanes in the campaign, wrote later: "I for one have never forgiven the Vichy French for the unnecessary slaughter they caused."

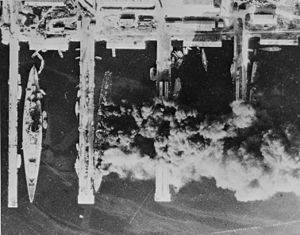

Most French forces abroad vigorously resisted the British. Smith describes bloody naval actions in which French destroyers and submarines were sunk in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean. The fighting was at its toughest in Madagascar, an almost forgotten campaign.

Even in November 1942, when it was becoming plain the Allies would win the war, French troops gave an unpleasant surprise to Americans landing in North Africa, treating them as invaders rather than liberators. They inflicted 1,500 US casualties before they ceased fire.

Why did they resist so fiercely? It may be difficult to understand but many French professional soldiers, sailors and airmen considered it their duty to serve their country as its government demanded, and accepted the legitimacy of Vichy.

Meanwhile, old Marshall Pétain remained a hero to many Frenchmen. April 1944 in Paris saw him given a rapturous reception after attending a Requiem Mass at Notre Dame, but the days of Vichy were numbered and after the Normandy landings the Germans marched out of Paris and the Allies liberated the city in triumph.

As the author explains, there was then a frantic flurry of invention in France about the liberation. France had been won back with some help from our "dear Allies" but the driving force was "all France" which was Gaullist. History was not only being made but re-written at a gallop.

The swift change of heart hit the old hero of Verdun very hard indeed. Found guilty of treason by a Gaullist court, increasingly senile and uncomprehending, he was confined to the bleak fortress island of Ile d'Yeu off the Atlantic coast where he died, aged 95, in 1951.

Then and now, France tried to forget that Vichy ever happened.

But it is not lost in the archives, nor in people's minds, and Smith's considerable achievement is to unmask the reality and make us understand this painful period far better than ever before.

Last edited: