ScienceRocks

Democrat all the way!

- Banned

- #21

Quite typical. Lets not transfer anymore of this into the western world...thanks.

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

BAMAKO, Mali This onetime model of African stability remained in a precarious state on Tuesday as the new military junta fought back an attempted countercoup by loyalist troops and asserted victory by days end.

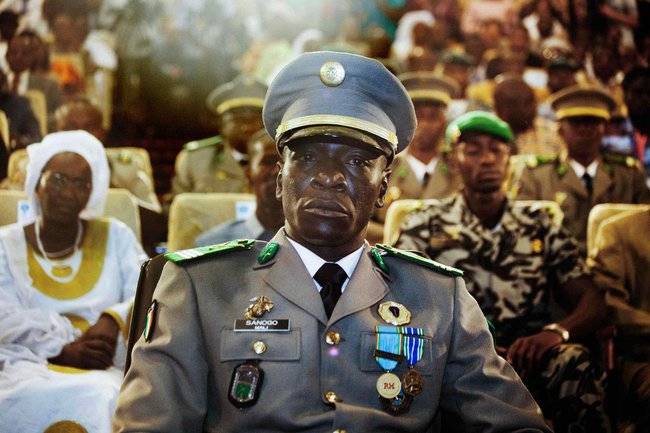

Hours before the revolt broke out Monday, the juntas leader, a youthful American-trained captain named Amadou Haya Sanogo confidently declared a leading role in Malis future in an interview at his barracks outside Bamako, the capital. There was no hint that his authority would be challenged later in the day, but soldiers were busy building a substantial protective wall in front of the dilapidated two-story military building that is his headquarters.

There were sporadic bursts of gunfire on a rainy May Day holiday, but soldiers on the street, diplomats and a high-ranking member of the junta said control had been re-established in Bamako, at least temporarily, after a night of shelling and tracer fire. Key positions the state television station, the airport and the loyalist Djicoroni barracks were under their command, said the soldiers, who appeared calm for the most part. Still, gunfire crackled over the Djicoroni barracks late into the afternoon.

The apparent triumph of Malis military bosses, less than six weeks after they chased the elected president from his palace overlooking the capital, seemed a further step in the consolidation of their control, despite pledges to restore civilian rule and democracy. It was a show of firepower, capped by the overrunning of the short-lived uprisings center in the Djicoroni barracks. The high-ranking member of the junta, who asked not to be quoted by name, said there had been deaths on both sides, but could not say how many.

Captain Sanogos coup on March 22 caused the immediate collapse of the Malian Armys resistance to nomadic rebel and Islamist forces sweeping across the vast northern half of the country. That area, now outside government control, has been the scene of serious human rights abuses, including rapes, public floggings and amputations, according to a Human Rights Watch report released Monday. The swift breakdown of the armed forces has led, in turn, to questions about the effectiveness of a United States-led regional counterterrorism program that had taken the Malian Army under its wing.

Across Bamako, somber black billboards have sprung up, depicting the map of Mali as a giant face shedding tears from its northern half, and with a big question mark planted in its southern section. Refugee accounts gathered by Human Rights Watch and clandestine footage aired on France 2 television depict a vast region of West Africa, including the historic city of Timbuktu, now under the repressive sway of militant Islamist factions like Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

A month ago, ethnic Tuareg fighters seized the northern stretches of Mali as it reeled from a coup, declaring a new state of their own called Azawad. Mali has so far failed to dislodge the rebels, but the Tuareg stab at independence has fallen flat internationally, winning scant support.

The would-be state has been rejected by the African Union, the European Union and the United States since it declared itself. The African Union shuns changing any borders, let alone creating new nations, as part of a pact agreed to decades ago to quash conflict.

"If that door opened, almost every ethnic group might want its own separate state," said Calestous Juma, professor of international development at the Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government. "Africa's road to hell is paved by tribal intentions. Nobody wants another Somalia."

Others have overcome the resistance of the African Union to new nations, most recently South Sudan. But whereas South Sudan came into being after a long civil war and was legitimized by an agreed-on referendum, Azawad emerged from sheer force and the power vacuum following the Mali coup.

Azawad is also seen skeptically because of its ethnic roots. Giving a Tuareg state the African Union's blessing could encourage ethnic minorities in neighboring nations to split away, or allow Azawad to spread into other countries with Tuareg populations.

Such a state is problematic in the first place: Although the rebels are Tuareg, much of the territory they claim is home to a diverse set of ethnic groups, especially toward the south. Exact numbers are elusive, but it is believed that only 3 million out of 14.5 million people in the northern stretches of Mali are Tuaregs, said J. Peter Pham, Africa director at the Atlantic Council.

"If you had a vote today about whether to break away, I don't think they'd [the rebels] win," said William Moseley, a University of Botswana visiting scholar. "It's not even clear if all the Tuaregs support that."

Adding to the wariness are fears that the new nation might not be economically viable, with few sources of food. The deserts may have oil deposits, but experts say it isn't clear how profitable they could be.

(Reuters) - West African bloc ECOWAS has opened talks with Mali's rebel groups, including fighters linked to al Qaeda, as part of its effort to restore constitutional rule in the country in the wake of its March 22 coup, Burkina Faso's foreign minister said.

The talks are the first publicly acknowledged negotiations with the armed groups by the regional bloc since a mix of separatist rebels and Islamist gunmen took control of northern Mali following the coup in the capital.

"We have to ensure that all factions feel involved in the peace process ... it is better for them all to be present at negotiating table," minister Djibril Bassole told journalists late on Thursday.

Burkina Faso is one of ECOWAS's lead mediators in the Mali crisis. Bassole gave no details on any progress made.

ECOWAS is trying to map out a political transition and has said that it has a 3,000-strong force ready to be deployed to Mali, though analysts have questioned the bloc's readiness and appetite for desert warfare against heavily armed rebels.

The two main groups occupying Mali's north are the Tuareg-led MNLA, which wants an independent state in the desert north, and Ansar Dine, an al Qaeda-linked group which is seeking to impose Islamic law, sharia, across Mali.

But other groups including AQIM, al Qaeda's North African wing, MUJWA, which is an AQIM splinter group, and foreign fighters are also operating in the area, fuelling regional fears it has become a haven for extremists and international criminal gangs.

ECOWAS has offered to help Mali retake control of its north but plans remain vague and, before any force comes to the country, the bloc will have to resolve the political crisis.

The current interim president's term runs out this weekend and the military has proposed a national convention to choose a successor, but regional leaders and many of the country's politicians have rejected the plan.

"It is about proposing a plan that brings together the transitional government, the armed groups and other actors to find a way out of this crisis," Bassole said.

BAMAKO, Mali Demonstrators forced their way into the office of Mali's interim president on Monday and attacked the elderly leader, who was later brought to a local hospital unconscious, a witness and an associate of the president said.

Dioncounda Traore was treated at the Point G Hospital for an injury to the head, said Sekou Yattara, a medical student there. The interim leader was not conscious when he arrived at the hospital though he regained consciousness later, Yattara added, explaining that he learned of the president's condition from the doctors treating him.

"He has been badly injured but the information I have is that his life is not in danger," said Iba N'Diaye, the vice president of Traore's party. "This was an attempt on his life."

Thousands of people descended on the presidential palace in Bamako on Monday morning, angry over a deal brokered by regional powers that extended the time Traore would stay in power.

The demonstrators carried sticks and branches from trees with which they hit portraits of Traore, others ripped photocopies of the interim president's photograph. One group carried a dummy wrapped in cloth lying on two long sticks, meant to represent Dioncounda's dead body.

Just months before it was to hold elections, Mali was thrown into chaos when soldiers staged a March 21 coup, driving the country's democratically elected leader into exile and reversing two decades of democratic rule in one of the only stable countries in this volatile patch of Africa.

Mali's neighbors reacted swiftly and the body representing nations in the region, the Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS, imposed strict sanctions until the junta agreed to restore the country's constitution in early April.

The constitution called for the head of the national assembly Dioncounda Traore to become interim president for a 40-day period, before new elections could be held. The 40-day window expired on Thursday, and ECOWAS wanted Traore's term extended for another year, in order to give the country time to properly plan elections. The junta leader agreed over the weekend to allow Traore's term to be extended in return for receiving a lifetime salary, and the status of a former head of state.

Even as officials on Monday were announcing the new deal, thousands of demonstrators allied with the soldiers that seized power poured into the streets, and made their way up the steep hill, known as Koulouba, where the presidential palace sits. It appears that they were able to penetrate the palace with the help of soldiers belonging to the junta.

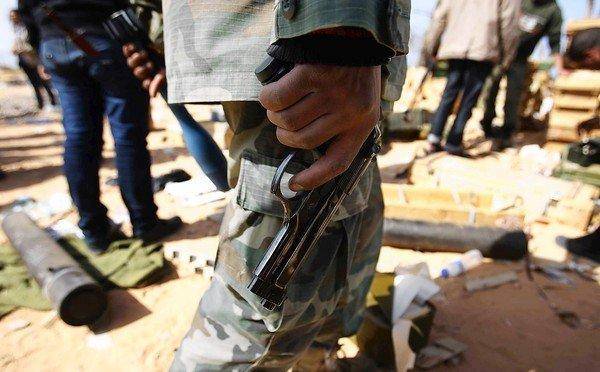

SABHA, Libya Abdallah takes out his pistol and hands it to a friend. He says he is in good company, so he does not need it.

Dressed in military camouflage gear and scarves, Abdallah and his six Libyan Tuareg companions sit under a tree that provides scant protection from the Saharan sun in southern Libya. They have been smuggling munitions to Tuareg insurgents in northern Mali for much of the last eight months.

"We know the desert; there is nobody who can stop us," says one of the men, Omar.

Since the beginning of last year's insurgency against longtime Libyan leader Moammar Kadafi, weapons have streamed out of Libya, looted from depots and sold on the black market. Difficult to track and impossible to quantify, they move in many directions.

Smugglers from Zintan in the northwest move south with ease into the remote regions straddling Chad and Niger, selling munitions to militants in the Sahel region south of the Sahara desert. Israeli officials say that weapons have flowed into the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip, pouring out from Egypt through tunnels. The North African-based Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, through long-established links to drug dealers and gunrunners, reportedly acquired Libyan arms as early as March 2011.

According to a United Nations report released in late January, smuggled weapons include "rocket-propelled grenades, machine guns with antiaircraft visors, automatic rifles, ammunition, grenades, explosives (Semtex), and light antiaircraft artillery (light-caliber bi-tubes) mounted on vehicles."

Substantial numbers of weapons have moved south, ending up in Mali, the report says, bought by Malian Tuareg mercenaries who fought for Kadafi.

Racked by drought and food shortages, the Sahara-Sahel strip is host to some of the world's busiest smuggling routes. People. Weapons. Colombian cocaine. All pass through this sweltering desert expanse.

The U.N. Security Council has called on Libya's interim authorities to take action to stem the flow of weapons, fearing transnational destabilization in the Sahel, which is experiencing a severe food crisis and political turmoil.

"We are concerned about the porous nature of the border between Chad, Niger and Libya and the risk of weapons, including MANPADS [shoulder-launched missiles capable of downing a low-flying airliner], moving across those borders," Rosemary DiCarlo, the U.S. deputy representative to the United Nations, said this year during a Security Council briefing in New York.

GENEVA The level of violence against children and cases of cholera in northern Mali are rising at an alarming rate since the area was seized by al-Qaida-linked Islamist fighters and Tuareg rebels following a March coup, U.N. officials said Friday.

At least 175 boys between the ages of 12 and 18 have been recruited into armed groups, at least eight girls were sexually assaulted and two teenage boys were killed by land mines and unexploded ordnance since the end of March, the U.N. children's agency UNICEF reported.

UNICEF spokeswoman Marixie Mercado said school closures in Mali have affected 300,000 children, making them more vulnerable to violence and recruitment as child soldiers.

"These numbers are reason for alarm especially because they represent only a partial picture of the child protection context in the north an area where access for humanitarian workers is limited," Mercado told reporters at the U.N.'s European headquarters in Geneva.

Jens Laerke, a spokesman for the U.N.'s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, said hospital officials in the northern Mali city of Gao told U.N. officials on Thursday that they had 24 cases of cholera.

Another clash with global consequences looms, apart from the awful conflagration in war-ravaged Syria. On Oct. 12, following weeks of French pressure, the U.N. Security Council set a 45-day deadline for intervention into Mali, the northwest African nation that has seen roughly half of its territory overrun by rebels and militias with links to al-Qaedas North African wing (AQIM). Frances Defence Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian insisted Tuesday it was a matter of weeks, not months before decisive action would be taken to reclaim a vast stretch of desert and semiarid scrubland that has become a terrorist sanctuary. The instability of the past half-year in Mali has sparked fears on both sides of the Mediterranean of a broader regional crisis. Six French nationals are currently being held hostage in the Sahel. Only the integrity of Mali, said Le Drian, assures Europes security.

Metaphors of doom now swirl in what was once one of Africas democratic success stories. Some say that Mali is the next Somalia, where a patchwork of warlords and insurgents ranges itself against a dysfunctional, crisis-hit state. Others say it is the next Afghanistan, where extremist militias, some with jihadist connections, make hay in a security vacuum, arming and funding themselves through illicit drug smuggling networks. (Islamist groups in control of historic Saharan entrepots such as the cities of Timbuktu and Gao have instituted Sharia law and, like the Afghan Taliban a decade ago, destroyed ancient tombs and relics considered idolatrous within their own puritanical creed.) And now it may be the next Libyawhere only foreign military intervention, framed as humanitarian action, can stabilize a steadily deteriorating state of affairs.

Still, despite the confidence of the French Defence Minister, concrete action looks far away. The U.N. Security Council resolution calls on the Malian government and ECOWAS, a bloc of West African states that includes Mali, to jointly prepare a plan to retake the countrys north. While ECOWAS nations all share concerns over the havoc in Mali spreading across its borders, there are pronounced deficits in trust between various parties. Moreover, as related in a report published in late September by the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank, the ECOWAS armies are accustomed mostly to conflict in forested areas and will need considerable help to launch a successful campaign in the Malian Sahel. The bloc, says the ICG report, displays a rhetorical ambition that goes beyond its capacity to deliver.

Why should Americans care about Mali? Many probably asked themselves that question during the last presidential debate, when Mitt Romney twice mentioned the northwest African nation, a place most Americans might be hard-pressed to locate on a map. Yet seven months after Islamic militant groups seized control of northern Mali, the Western-designed military strategy to push them out could have real consequences for future antiterrorist operations, including for the U.S., according to some analysts. As the pieces steadily fall into place for a military assault on northern Mali, the intervention could serve as a model for future conflicts, at a time when Americans and Europeans have no appetite to fight another war. Were moving to a form of intervention which is much more typical of the post-Afghanistan era than anything we have seen before, says François Heisbourg, a special advisor to the Foundation for Strategic Research in Paris. If you are looking at future military interventions, it will not be like Iraq and Afghanistan.

The objective is clear: to seize back control of northern Mali an area the size of Texas and crush the Islamic militants who have controlled it since last April. As a measure of how urgent the West believes the situation is, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton landed in Algiers on Monday to try to lock in President Abdelaziz Bouteflikas support for a military assault across his border, with an aide telling reporters on the plane headed to Algerias capital that the country was a critical partner in dealing with al-Qaeda in North Africa. And last Wednesday U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta told reporters in Washington that the U.S. had to ensure that al-Qaeda has no place to hide and that we have to continue to go after them.

That will not be easy especially since no Western troops will be deployed on the ground. The plan, crafted in a frenzy of diplomatic activity in Africa during the past two weeks, will instead rely on about 3,200 West African troops, together with 3,000 Malian troops trained by the E.U. Many of the West African troops are Nigerian, who have little experience in fighting across the remote, vast desert that characterizes northern Mali. In a French-led resolution at the U.N. on Oct. 12, African countries have until late November to craft a plan to get the Islamic groups out of northern Mali. Behind the scenes, U.S. and French Special Forces are increasingly involved in training and advising African militaries, according to Heisbourg, in advance of the attack, which could come early next year. And French officials have said they would likely deploy unarmed surveillance drones of the kind the U.S. already has at hand in the area.