Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Origin of our species

- Thread starter waltky

- Start date

- Thread starter

- #22

Granny says, "Dat's right - first white man found...

Researchers reveal Europeans' fourth ancestral 'tribe'

Nov. 16, 2015 - The Caucasus population was well-positioned to influence the peoples of both Europe and Asia, and studying them further is likely to bring further revelations.

Researchers reveal Europeans' fourth ancestral 'tribe'

Nov. 16, 2015 - The Caucasus population was well-positioned to influence the peoples of both Europe and Asia, and studying them further is likely to bring further revelations.

The origins of modern Europeans' genetic makeup is becoming clearer. Scientists have found the "fourth strand" of European ancestry. A small but significant portion of Europe's genome is derived from a unique population of hunter-gatherers who for several thousand years sat out the frigid intolerance of the Ice Age in the shelter of the Caucasus mountains. Shortly after the Out of Africa movement, a group of hunter-gatherers split off from western populations and settled the lands along the present day Russian-Georgian border. There, hemmed in by ice and snow, they remained isolated for several thousand years, their genetic makeup growing more distinct.

DNA extracted from 10,000-year-old skeletal remains, found in the Caucasus Mountains, have revealed the "fourth strand" of European ancestry.

At some point after the the last Ice Age finally began to recede, approximately 22,000 years ago, the Caucasus peoples joined the Yamnaya culture, the horse-borne Steppe herders of Eastern Europe. Around 5,000 years ago, the Yamnaya culture swept into Western Europe. They brought considerable metal-working skills with them, and some anthropologists believe their arrival ushered in the Bronze Age. They also brought the family of Indo-European languages that would birth the tongues of modern Europe. Central and Northern Europe owe as much as half of their ancestry to the Yamnaya herders. Researchers have long been aware the Yamnaya's influence of Europe's genome and vocabulary, but the Steppe herders themselves were a mixed people. The latest discovery, made possible by sequencing ancient genomes from the Caucasus region, shows where exactly some of that mixing came from.

The DNA was extracted from skeletal remains found in the caves of Western Georgia. The remains dated between 10,000 and 13,000 years old. "The question of where the Yamnaya come from has been something of a mystery up to now," Andrea Manica, from Cambridge's zoology department, said in a press release. Manica is one of the lead authors of a new paper on the discovery, published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

MORE

Delta4Embassy

Gold Member

DNA Evidence Suggests Man 340,000-Years-Old...

The family tree that rewrote human history: Researchers stunned to find DNA submitted to online project dates back 338,000 years

7 March 2013 | Discovery made after American submitted his DNA to a family tree service; DNA traced to Mbo, a population living in a tiny area of western Cameroon; Proves last common Y chromosome ancestor lived 338,000 years ago, even though oldest fossil of modern man is only 200,000 years old

A DNA test on an American hoping to trace his family tree has come up with a stunning result - the roots of the human tree date back much further than previously thought. Researchers were shocked when they analysed the DNA of Albert Perry, a recently deceased African-American from South Carolina. 'This lineage diverged from previously known Y chromosomes about 338,000 years ago, a time when anatomically modern humans had not yet evolved,' said Michael Hammer of the University of Arizona. "This pushes back the time the last common Y chromosome ancestor lived by almost 70 percent.'

This time predates the age of the oldest known anatomically modern human fossils. The fossil record dates back about 200,000 years, said Hammer. Either interbreeding with Neanderthals or other populations led to the unusual genetic makeup, he said, or humans evolved far earlier than the extant fossil record suggests. The new divergent lineage - which was found when Mr Perry contacted Family Tree DNA, a company specializing in DNA analysis to trace family roots - branched from the Y chromosome tree before the first appearance of anatomically modern humans in the fossil record.

The team found a similar chromosome in the Mbo, a population living in a tiny area of western Cameroon in sub-Saharan Africa

Unlike the other human chromosomes, the majority of the Y chromosome does not exchange genetic material with other chromosomes, which makes it simpler to trace ancestral relationships among contemporary lineages. If two Y chromosomes carry the same mutation, it is because they share a common paternal ancestor at some point in the past. The more mutations that differ between two Y chromosomes the farther back in time the common ancestor lived. The results are published in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Originally, Mr Perry's DNA sample was submitted to the National Geographic Genographic Project. When none of the genetic markers used to assign lineages to known Y chromosome groupings was found, the DNA sample was sent to Family Tree DNA for sequencing. Fernando Mendez, a postdoctoral researcher in Hammer's lab, led the effort to analyze the DNA sequence, which included more than 240,000 base pairs of the Y chromosome. Hammer said: 'The most striking feature of this research is that a consumer genetic testing company identified a lineage that didn't fit anywhere on the existing Y chromosome tree, even though the tree had been constructed based on perhaps a half-million individuals or more. 'Nobody expected to find anything like this.'

Read more: The family tree test that rewrote human history: Researchers stunned to find DNA submitted to online service dates back 338,000 years | Mail Online

Was this before or after Adam and Eve then?

DNA can't in any way be used to chronologically date anything.

Punctuated equilibrium - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In fact, the more complex the organism, the more uncertain any timeline will be.

Punctuated equilibrium - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In fact, the more complex the organism, the more uncertain any timeline will be.

- Thread starter

- #25

Mysterious tool makers inhabited Sulawesi 118,000 years ago...

Ancient tools show mysterious humans occupied Indonesian island

13 Jan.`16 WASHINGTON - The diminutive prehistoric human species dubbed the "Hobbit" that inhabited the isle of Flores apparently had company on other Indonesian islands long before our species, Homo sapiens, arrived on the scene.

Ancient tools show mysterious humans occupied Indonesian island

13 Jan.`16 WASHINGTON - The diminutive prehistoric human species dubbed the "Hobbit" that inhabited the isle of Flores apparently had company on other Indonesian islands long before our species, Homo sapiens, arrived on the scene.

Scientists on Wednesday announced the discovery of stone tools at least 118,000 years old at a site called Talepu on the island of Sulawesi, indicating a human presence. The scientists said no fossils of these individuals were found in conjunction with the tools, leaving the toolmakers' identity a mystery. "We now have direct evidence that when modern humans arrived on Sulawesi, supposedly between 60,000 and 50,000 years ago and aided by watercraft, they must have encountered an archaic group of humans that was already present on the island long before," said archaeologist Gerrit van den Bergh of University of Wollongong in Australia.

Surface-collected stone artefacts that were found lying scattered on the gravelly surface near Talepu on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi

The 2004 announcement of the discovery in a Flores cave of fossils of Homo floresiensis, a species about 3 feet 6 inches (1.1 meter) tall that made tools and hunted little elephants, jolted the scientific community. "Like on Flores, where Homo floresiensis evolved under isolated conditions over a period of almost 1 million years, Sulawesi could also have harbored an isolated human lineage. And the search for fossil remains of the Talepu toolmaker is now open," van den Bergh said.

Scientists have been eager to unravel the region's history of human habitation. Sulawesi may have served as a stepping stone for the first people to reach Australia roughly 50,000 years ago. "Major islands such as Flores, Sulawesi, Luzon, and perhaps others as well, could have served as natural experiments in human evolution, and could throw new light on human evolution in general," van den Bergh added. The species that made the tools may have reached Sulawesi by drifting over the ocean on tsunami debris, he said.

The Walanae River at Paroto, east of Talepu on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi

The researchers described 311 stone tools, most made of a very hard limestone. Archaeologist Adam Brumm of Australia's Griffith University said they were produced by humans striking one stone with another, fashioning smaller pieces with knife-like sharpness. "They mostly comprise simple sharp-edged flakes of stone that no doubt would have been useful for basic tasks like cutting up meat, shaping wooden implements, and so on," Brumm said. Found nearby were fossils of an extinct elephant relative and extinct giant pig with warthog-like tusks. The research was published in the journal Nature.

Ancient tools show mysterious humans occupied Indonesian island

- Thread starter

- #26

Diggin' up an ol' woolly mammoth carcass in Russia...

Ancient people conquered the Arctic at least 45,000 years ago

14 Jan.`16 | WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The frozen carcass of a woolly mammoth found in Siberia with unmistakable signs of spear wounds is providing evidence that people inhabited Arctic regions thousands of years earlier than previously known.

Ancient people conquered the Arctic at least 45,000 years ago

14 Jan.`16 | WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The frozen carcass of a woolly mammoth found in Siberia with unmistakable signs of spear wounds is providing evidence that people inhabited Arctic regions thousands of years earlier than previously known.

Russian scientists on Thursday said the male mammoth excavated from a bluff on Yenisei Bay on the Arctic Ocean was killed by hunters 45,000 years ago, providing the earliest indication of the presence of humans in the Arctic. Until now, the oldest evidence of humans in Arctic regions dated to "more or less 30,000 years ago," according to Vladimir Pitulko, senior research scientist at the Russian Academy of Sciences' Institute for the History of Material Culture in St. Petersburg.

Researcher Sergey Gorbunov is shown working on the excavation of a woolly mammoth carcass from frozen sediments on a coastal bluff on the eastern shore of Yenisei Bay in the central Siberian Arctic, in this undated handout photo provided by Alexei Tikhonov, Director of Zoological Museum, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia

The people who endured the harsh Arctic conditions likely lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, Pitulko said. Mammoths, the close elephant relatives that were the largest land creatures in the region, represented an important resource for them. "Indeed, these animals provide an endless source of different goods: food with meat, fat and marrow; fuel with dung, fat and bones; and raw material with long bones and ivory," Pitulko said. "They certainly would use them as food, especially certain parts like tongue or liver as a delicacy, but hunting for the ivory was more important," added Pitulko, with the ivory substituting for wood in the treeless steppe landscape.

The mammoth, excavated in 2012, had injuries indicating it had been killed by people. Damage to its ribs appears to have been caused by spears thrown by hunters, while shoulder-blade and cheekbone injuries probably came from hand-held thrusting spears, Pitulko added. There also was damage to the right tusk that may have been caused by people chopping at it after the mammoth was killed. "The main part of it is that the mammoth was really killed by humans, and evidence for that is unbeatable," Pitulko said.

This frozen woolly mammoth changes human history

Scientists think mammoth-hunting may have been a critical factor in enabling people to survive in the Arctic and trek across northernmost Siberia, helping them reach the vicinity of the Bering land bridge that at the time linked Siberia to Alaska. The first humans to reach the New World crossed that land bridge, then spread through the Americas. The fact that humans populated Arctic regions sooner than previously known suggests the possibility that people also crossed the Bering land bridge earlier than currently suspected, Pitulko added. The research was published in the journal Science.

Ancient people conquered the Arctic at least 45,000 years ago

Old Rocks

Diamond Member

Just had my DNA done by 23andme. Turns out I am at least 4% neanderthal. Wife said she thought it would be far higher than that.

- Thread starter

- #28

Transitional species of humans found...

Early human ancestor didn't have a nutcracker jaw

Feb. 8, 2016 - "Humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully," explained researcher Justin Ledogar.

Early human ancestor didn't have a nutcracker jaw

Feb. 8, 2016 - "Humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully," explained researcher Justin Ledogar.

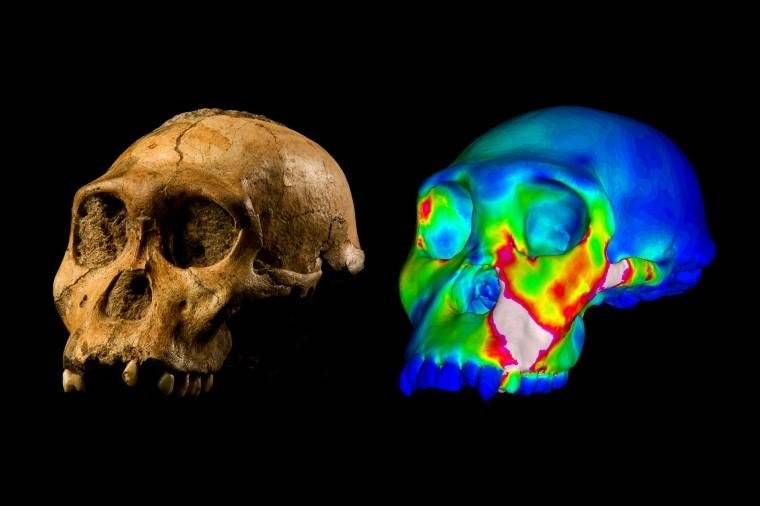

In 2012, a team of scientists published a paper suggesting Australopithecus sediba, an early human ancestor, subsisted on mostly on hard foods including tree bark, nuts, fruits and leaves. But even if early hominids had the stomach for such a diet, they didn't have the jaw. A new study published in the journal Nature Communications suggests biting on hard foods like bark or shelled nuts would have risked dislocating the jaw of A. sediba.

Scientists at Washington University in St. Louis say the hominid didn't have the nutcracker jaw that its predecessors possessed. The new evidence supports the assertion that A. sediba was a transitional species between A. africanus and either Homo habilis or the later H. erectus. "Most australopiths had amazing adaptations in their jaws, teeth and faces that allowed them to process foods that were difficult to chew or crack open," lead researcher David Strait, a professor of anthropology at WUSTL, said in a news release. "Among other things, they were able to efficiently bite down on foods with very high forces."

An image from one of the simulations used to identify structural weak points in the jaw of Australopithecus sediba.

"A. sediba had an important limitation on its ability to bite powerfully," added Justin Ledogar, a former graduate student of Strait and now a researcher at the University of New England in Australia. "If it had bitten as hard as possible on its molar teeth using the full force of its chewing muscles, it would have dislocated its jaw." To test the sturdiness of the hominid's jaw, researchers subjected a skull found in 2008 in South Africa to a series of biomechanical tests and modeling simulations similar to those used to measure the strength of car and airplane components.

Previous assumptions about the eating habits of A. sediba are based on evidence of teeth damage. While the early hominid may have eaten some hard foods, the new research suggests it wasn't adapted to do so, and likely relied more heavily on foods that were easier to chew. "Humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully and we suspect that early Homo had it as well, yet the other australopiths that we have examined are not nearly as limited in this regard," Ledogar said. "This means that whereas some australopith populations were evolving adaptations to maximize their ability to bite powerfully, others -- including A. sediba -- were evolving in the opposite direction."

Early human ancestor didn't have a nutcracker jaw

Steven_R

Tommy Vercetti Fan Club

- Jul 17, 2013

- 4,852

- 924

- 245

'

Pure clap-trap. Natural evolution is dead.

From now on, human evolution will be artificially engineered.

We will have travelled far down the road to becoming cyborgs in decades, not in millennia !!

.

I, for one, can't wait to become more machine now than man, twisted and evil...

Steven_R

Tommy Vercetti Fan Club

- Jul 17, 2013

- 4,852

- 924

- 245

At this stage of human development I am much more interested in humanity's final destination than its original starting point.

Eloi and morlocks?

- Thread starter

- #31

Understanding the Denisovans...

How extinct humans left their mark on us

Fri, 18 Mar 2016 - Most of us share 2-4% of DNA with Neanderthals; some have genes from Denisovans; but their genetic mark has vanished in some stretches of genetic code.

See also:

DNA of girl from Denisova cave gives up genetic secrets

31 August 2012 - The DNA of a cave girl who lived about 80,000 years ago has been analysed in remarkable detail.

How extinct humans left their mark on us

Fri, 18 Mar 2016 - Most of us share 2-4% of DNA with Neanderthals; some have genes from Denisovans; but their genetic mark has vanished in some stretches of genetic code.

Most people in the world share 2-4% of DNA with Neanderthals while a few inherited genes from Denisovans, a study confirms. Denisovan DNA lives on only in Pacific island dwellers, while Neanderthal genes are more widespread, researchers report in the journal Science. Meanwhile, some parts of our genetic code show little trace of our extinct cousins. They include hundreds of genes involved in brain development and language. "These are big, truly interesting regions," said co-researcher Dr Joshua Akey, an expert on human evolutionary genetics from the University of Washington Medicine, US. "It will be a long, hard slog to fully understand the genetic differences between humans, Denisovans and Neanderthals in these regions and the traits they influence."

Siberia cave Studies of nuclear DNA (the instructions to build a human) are particularly useful in the case of Denisovans, which are largely missing from the fossil record. The prehistoric species was discovered less than a decade ago through genetic analysis of a finger bone unearthed in a cave in northern Siberia. Substantial amounts of Denisovan DNA have been detected in the genomes of only a handful of modern-day human populations so far. "The genes that we found of Denisovans are only in this one part of the world [Oceania] that's very far away from that Siberian cave," Dr Akey told BBC News.

Where the ancestors of modern humans might have had physical contact with Denisovans is a matter of debate, he added. Denisovans may have encountered early humans somewhere in South East Asia and, eventually, some of their descendants arrived on the islands north of Australia. Meanwhile, humans repeatedly ran into Neanderthals as they spread across Eurasia. "We still carry a little bit of their DNA today," said Dr Akey. "Even though these groups are extinct their DNA lives on in modern humans."

Genetic ancestry

The research was carried out by several scientists, including Svante Paabo of the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Max-Planck-Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. They found that all non-African populations inherited about 1.5-4% of their genomes from Neanderthals. However, Melanesians were the only population that also had significant Denisovan genetic ancestry, representing between 1.9% and 3.4% of their genome. "I think that people (and Neanderthals and Denisovans) liked to wander," said Benjamin Vernot of the University of Washington, who led the project. "And yes, studies like this can help us track where they wandered."

How extinct humans left their mark on us - BBC News

See also:

DNA of girl from Denisova cave gives up genetic secrets

31 August 2012 - The DNA of a cave girl who lived about 80,000 years ago has been analysed in remarkable detail.

The picture of her genome is as accurate as that of modern day human genomes, and shows she had brown eyes, hair and skin. The research in Science also sheds new light on the genetic differences between modern humans and their closest extinct relatives. The cave dweller, a Denisovan, was a cousin of the Neanderthals. Both groups of ancient humans died out about 30,000 years ago, but have left their mark in the gene pool of modern people.

Shadowy past

The Denisovans have mysterious origins. They appear to have left little behind for palaeontologists save a tiny finger bone and a wisdom tooth found in Siberia's Denisova cave in 2010. Though some researchers have proposed a possible link between the Denisovans and human fossils from China that have previously been difficult to classify. A Russian scientist sent a fragment of the bone from Siberia to a team led by Svante Paabo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. He thought it might belong to an early modern human, but the results came as a surprise.

DNA analysis revealed a human who was neither a Neanderthal nor a modern human but the first of a new group of ancient humans. Gene catalogue Dr Paabo's team has now sequenced the genome of the Denisovan in much greater depth, using a new technique for studying ancient DNA. The quality of the genome sequence is similar to that seen in genome studies of modern day humans. "This is an extinct genome sequence of unprecedented accuracy," said Dr Matthias Meyer, the chief researcher on the study. "For most of the genome we can even determine the differences between the two sets of chromosomes that the Denisovan girl inherited from her mother and father." The scientists compared the girl's genome with that of Neanderthals and 11 modern humans from around the world.

This allowed them to catalogue the gene changes that make modern humans different from the two groups of extinct humans that were their closest relatives. They include changes to only a single DNA letter in several genes involved in the wiring of the brain and nervous system, as well as those that affect the eye and the skin. Dr Paabo said further investigation of changes in genes involved in connecting up the brain will be exciting to pursue. He told BBC News: "To me the most exciting thing is having a good genome from our very closest extinct relatives which we can now compare ourselves to. "It's a catalogue of what makes everyone on the planet unique compared with our closest extinct relatives."

The most detailed genetic analysis yet of the Denisovans also confirms that they bred with the ancestors of some people alive today, the researchers said. It shows that about 3% of the genes of people living today in Papua New Guinea come from Denisovans, with a trace of their DNA lingering in the Han and Dai people from mainland China. The genetic variation of Denisovans was very low, suggesting that although they were found in large parts of Asia their population remained small.

DNA of girl from Denisova cave gives up genetic secrets - BBC News

- Thread starter

- #32

Ancient artifacts found in Florida sinkhole...

Early snowbirds? Florida sinkhole yields ancient artifacts

May 13, 2016 — Scientists say a stone knife and other artifacts found deep underwater in a Florida sinkhole show people lived in that area some 14,500 years ago.

See also:

Findings Push Human Timeline in US Back a Millennium

May 13, 2016 - A new trove of carbon-dated archaeological evidence from a submerged site in Florida has some big implications for the history of human beings in the Americas.

Early snowbirds? Florida sinkhole yields ancient artifacts

May 13, 2016 — Scientists say a stone knife and other artifacts found deep underwater in a Florida sinkhole show people lived in that area some 14,500 years ago.

That makes the ancient sinkhole the earliest well-documented site for human presence in the southeastern U.S., and important for understanding the settling of the Americas, experts said. The findings confirm claims made more than a decade ago about the site, some 30 miles southeast of Tallahassee. At that time, researchers reported evidence that humans were there some 14,400 years ago. But in an era when such an old date was widely considered impossible, other experts disputed the evidence, said Mike Waters of Texas A&M University in College Station. The sinkhole was "just politely ignored," he said. Waters was among a new team of scientists who excavated there from 2012 to 2014. They report finding the knife and stone flakes in a paper released Friday by the journal Science Advances. The new work offers "far better" evidence for early humans than the earlier research did, he said.

The sinkhole is nearly 200 feet wide. In ancient times, it had a shallow pond at the bottom. That offered fresh water and a gathering point for animals, which "probably would have been easy pickings" for hunters who saw them trapped in the deep depression, Waters said. Today, the sinkhole is filled with about 30 feet of water, and it took divers equipped with head-mounted lights to look for artifacts. It was "as dark as the inside of a cow, literally no light at all," said Jessi Halligan, the lead diving scientist and an assistant professor of anthropology at Florida State University in Tallahassee. They found the knife while digging with a trowel. It's a couple of inches long and about an inch wide, sharpened on both sides. To determine its age, the researchers used nearby mastodon dung, which contained twigs that could be analyzed. The twigs, and therefore the knife, were found to be about 14,550 years old.

In this 2015 photo provided by Texas A&M's Center for the Study of the First Americans, divers investigate the Page-Ladson archaeological site in Florida. Scientists say artifacts found deep underwater in a Florida sinkhole show people lived in that area some 14,500 years ago. That makes it the earliest well-documented site for human presence in the southeastern U.S., and important for understanding the settling of the Americas, experts said

Man-made stone flakes were found to be about the same age. The scientists also examined a mastodon tusk recovered in 1993, and confirmed that its long, deep grooves were made by people, probably as they worked to remove the tusk from a skull. The first people in North America are thought to have crossed a now-submerged land bridge from Siberia to Alaska. From there, people spread southward. Waters said the age of the sinkhole artifacts adds to evidence that people may have migrated south from Alaska as early as 16,000 years ago by boat along the coast, because inland Canada was blocked by ice sheets until 2,000 years later. Halligan said the ancient visitors to the sinkhole could have been the Southeast's first snowbirds, moving south for the winter and north for the summer. They could have followed mastodons, whose remains have been found as far north as Kentucky, she said. "They were very smart about local plants and local animals and migration patterns," she said.

In American archaeology, sites showing signs of human presence more than about 13,000 years are called "pre-Clovis," since they predate the Clovis era of widespread human occupation. Dennis Stanford of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History said that he ranked the sinkhole with two locations in Pennsylvania and Virginia as "the best-dated and oldest pre-Clovis sites yet found in North America." While the other two sites are older, "the Florida site has a major role to play in learning the story of the peopling of the Americas," said Stanford, who didn't participate in the research. Another expert, James Adovasio of Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton agreed, saying it promises to shed light on "early Native American lifestyle in an environment where these lifestyles are very poorly defined."

Early snowbirds? Florida sinkhole yields ancient artifacts

See also:

Findings Push Human Timeline in US Back a Millennium

May 13, 2016 - A new trove of carbon-dated archaeological evidence from a submerged site in Florida has some big implications for the history of human beings in the Americas.

Researchers from several U.S. universities say their work suggests humans were wandering around Florida about 1,000 years earlier than previously thought. Their study, published in the journal Science Advances, also paints a fascinating picture of what life in the Americas was like over 14,000 years ago. The new evidence comes from an underwater archaeological site called Page-Ladsen that has been giving up human and animal artifacts for over 50 years. Previous carbon dating of the objects brought up from murky waters put them anywhere between 11,000 and 13,000 years old.

A mastodon tusk (partially reassembled) from the Page-Ladsen site; curvature is typical for an upper tusk from the left side

But a team that dived back into the site came up with some new artifacts that date to a much earlier time — 14,550 years ago. That makes it one of the oldest sites in the Southeast, and the oldest submerged site in the Americas. And it pushes back current thinking on when humans were in this area by well over 1,000 years. These people were there well before the Clovis hunters, a prehistoric Paleo-Indian culture that was previously thought to be the most ancient human group living in North America. There has always been tantalizing archaeological and genetic evidence that humans had been in the region earlier than thought, but until now it could not be proven because so few older remains had been uncovered.

Neil Puckett, a doctoral student from Texas A&M University involved in the excavations, surfaces with the limb bone of a juvenile mastodon.

In a teleconference, the scientists suggested that changing sea levels might be the reason more evidence of these ancient Americans hadn't been found. Jessi Halligan, one of the researchers from Florida State University, said during the call that sea levels 14,000 years ago were 100 meters lower than they are today because of extensive glaciering. That means much of the earliest record of human habitation of the American Southeast is likely buried and underwater. The researchers' evidence is contained in stone tools and mastodon bones brought up from the 8-meter-deep sinkhole in the Aucilla River in Florida. They said the tools were clearly used to butcher the mastodon alongside a watering hole that, 15,000 years ago, would have been 200 kilometers from the shoreline. Today, it is the coastline.

Co-principal investigator Michael R. Waters and CSFA student Morgan Smith examine a biface, or bifacial stone tool, in the field after its discovery.

As further evidence that this population was a separate culture from the Clovis people, the researchers in their teleconference pointed to distinct differences between the stone tools they recovered and the flaked points of Clovis culture tools. In addition to pushing back the frontier of human colonization of the Americas, the evidence also paints a picture of a much different world. Fourteen thousand years ago, camels, mastodons and giant armadillo-like animals called Glyptodons, to name a few, lived in the area in abundance. Another tantalizing discovery are bones the researchers believe are from dogs, which even back then are likely to have been trained companions. But the dogs disappeared about 10,000 to 11,000 years ago. The humans, resilient as always, stayed, survived and thrived.

Findings Push Human Timeline in US Back a Millennium

numan

What! Me Worry?

- Mar 23, 2013

- 2,125

- 241

- 130

'

Pure clap-trap. Natural evolution is dead.

From now on, human evolution will be artificially engineered.

We will have travelled far down the road to becoming cyborgs in decades, not in millennia !!

.

I, for one, can't wait to become more machine now than man, twisted and evil...

For all we know, Artificial Intelligence and cyborgs may be more decent and spiritual than we are.

.

- Thread starter

- #34

Granny says dat was a bit before her time...

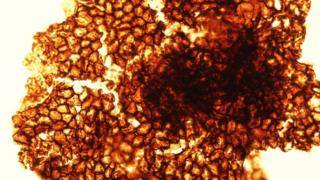

Life 'went large' a billion years ago

Tue, 17 May 2016 - Life was already organising itself into large communities of cells more than a billion years ago, new evidence from China suggests.

Life 'went large' a billion years ago

Tue, 17 May 2016 - Life was already organising itself into large communities of cells more than a billion years ago, new evidence from China suggests.

The centimetre-scale life forms were preserved in mudstones from the Yanshan area in the country's north and are dated to 1.56 billion years ago. Fossils big enough to be seen by the naked eye became common between 635 and 541 million years ago. But the latest specimens are more than twice that age. The findings by a Chinese-American team of researchers appear in the journal Nature Communications. The mysterious organisms from the Gaoyuzhuang rock formation appear to belong to the branch of life known as the eukaryotes, which today includes everything from single-celled amoebae to plants, fungi and animals. The sea-dwelling life forms probably lived on the shelf areas of ancient oceans and bear a superficial resemblance to algae. They also appear to have used photosynthesis, the process by which plants, some bacteria and other simple organisms convert sunlight into chemical energy.

Macroscopic fossils

Prof Andrew Knoll, from Harvard University, a co-author of the paper, said the organism represented by the Chinese fossils was "large but I doubt that it was complicated - an important distinction". He told me: "You're a good example of a complex multi-cellular organism because you have 250 cell types, dozens of tissues, different organ systems. "On the other hand if you go to the beach you will find seaweeds that consist of a sheet of cells that are almost all identical. Most of them can either photosynthesise or be used for reproduction." The team, including Prof Knoll and Shixing Zhu from the China Geological Survey in Tianjin, found that life in this ancient period had already developed a variety of forms. Of 53 separate specimens, 26 (49%) were linear in shape, 16 (30%) were wedge-shaped, eight (15%) were tongue-shaped and three (6%) were oblong-shaped. The marine organisms measured up to 30cm in length and up to 8cm wide. Some of the specimens revealed fine structure: a closely-packed arrangement of individual cells measuring about 10 micrometres long - which is the same as the width of cotton fibre.

Go big or go home

Examples of multi-cellular life dating back more than a billion-and-a-half years have been described before. They include Horodyskia, which was shaped like a strings of beads, and Grypania, a coiled, ribbon-like organism. But the diversity of forms and the size of the fossils from Yanshan mark them out. The researchers say the fossils are unlikely to be of agglomerations of bacteria known as microbial mats, and instead are probably early examples of eukaryotic organisms. If so, the organisms suggest multi-cellularity was a feature of marine life a billion years before the so-called Cambrian explosion, a rapid evolutionary event that began 542 million years ago and resulted in the divergence of major animal groups. Some scientists partly attribute this evolutionary flowering to a rise in oxygen levels, although the causes are the matter of continuing debate. The findings also suggest that the preceding era, characterised by lower oxygen levels and sometimes referred to as the "boring billion", may have been misjudged.

Prof Knoll told BBC News: "It looks like the leap from single cells to simple multi-cellularity is easy - in relative terms. It was done many times (over the course of evolution) and this really cements the case that it was done early in the history of eukaryotes. "There are a couple of cases where we know the genomes of both unicellular (single-celled) organisms and their closest multi-cellular relatives. When the jump is from a single cell to simple multi-cellularity, there's very little difference in the gene content of the organism. That's a small leap forward. "The difference when you go from simple multi-cellularity to complex multi-cellularity, however, is large. The tree of life suggests that has happened only rarely." However, the team was not able to link the fossils with any other known group of eukaryotes - living or extinct.

Life forms 'went large' a billion years ago - BBC News

- Thread starter

- #35

How long has our species been around?...

Discovery in Morocco alters history of Homo sapiens

Jun 7, 2017, How long has our species been around? New fossils from Morocco push the evidence back by about 100,000 years.

Discovery in Morocco alters history of Homo sapiens

Jun 7, 2017, How long has our species been around? New fossils from Morocco push the evidence back by about 100,000 years.

The bones, about 300,000 years old, were unearthed thousands of miles from the previous record-holder, found in fossil-rich eastern Africa. The new discovery reveals people from an early stage of our species' evolution, with a mix of modern and more primitive traits. "They are not just like us," said Jean-Jacques Hublin, one of the scientists reporting the find. But they had "basically the face you could meet on the train in New York." Coupled with other evidence, the Moroccan fossils suggest that Homo sapiens may have reached its modern-day form in more than one place within Africa, said Hublin, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and the College of France in Paris.

Previously, the oldest known fossils clearly from Homo sapiens were from Ethiopia, at about 195,000 years old. It's not clear just when or where Homo sapiens came on the scene in Africa. Hublin said he thinks an earlier stage of development preceded the one revealed by his team's discovery. We evolved from predecessors who had differently shaped skulls and often heavier builds, but were otherwise much more like us than, say, the ape-men that came before them. Our species lived at the same time as some related ones, like Neanderthals, but only we survive. Hublin and others described the new findings in two papers released Wednesday by the journal Nature . The discovery could help illuminate how our species evolved, Chris Stringer and Julia Galway-Witham of the Natural History Museum in London wrote in a Nature commentary.

The Moroccan specimens were found between 2007 and 2011 and include a skull, a jaw and teeth, along with stone tools. Combined with other bones that were found there decades ago but not correctly dated, the fossil collection represents at least five people, including young adults, an adolescent and a child of around 8 years old. Analysis shows their brain shape was more elongated than what people have today. "In the last 300,000 years, the main story is the change of the brain," Hublin said. When these ancient people lived, the site in Morocco was a cave that might have served as a hunting camp, where people butchered and ate gazelles and other prey. They used fire and their tools were made of flint from about 25 miles (40 kilometers) away.

So where did the fully modern human body develop? The researchers say evidence suggests primitive forms of Homo sapiens had already widely spread throughout Africa by around 300,000 years ago. The different populations may have exchanged beneficial genetic mutations and behaviors, gradually nudging each other toward a more modern form of the species, Hublin said. In this way, he said in an interview, modern Homo sapiens may have arisen in more than one place. So if there's a Garden of Eden, he said, it's the continent as a whole. Some experts who didn't participate in the research called that idea possible, although not yet demonstrated. But John Shea, an anthropologist at Stony Brook University in New York, said it's more useful to think of the different local populations as a single one, connected the same way a big city is connected by subway stops. "These are parts of a network," through which ideas and genes flowed, he said.

MORE

- Thread starter

- #37

The most complete skeleton of a human ancestor older than 1.5 million years ever found...

3.6-million-year-old human skeleton found, shocking scientists

8 Dec.`17 — Researchers in South Africa have unveiled what they call “by far the most complete skeleton of a human ancestor older than 1.5 million years ever found.”

3.6-million-year-old human skeleton found, shocking scientists

8 Dec.`17 — Researchers in South Africa have unveiled what they call “by far the most complete skeleton of a human ancestor older than 1.5 million years ever found.”

The University of the Witwatersrand displayed the virtually complete Australopithecus fossil on Wednesday. The skeleton dates back 3.6 million years. Its discovery is expected to help researchers better understand the human ancestor’s appearance and movement. The researchers say it has taken 20 years to excavate, clean, reconstruct and analyse the fragile skeleton.

The skeleton, dubbed Little Foot, was discovered in the Sterkfontein caves, about 40 kilometres northwest of Johannesburg when small foot bones were found in rock blasted by miners. Professor Ron Clarke and his assistants found the fossils and spent years to excavate, clean, analyse and reconstruct the skeleton.

The discovery is a source of pride for Africans, said Robert Blumenschine, chief scientist with the organisation that funded the excavation, the Paleontological Scientific Trust (PAST). “Not only is Africa the storehouse of the ancient fossil heritage for people the world over, it was also the wellspring of everything that makes us human, including our technological prowess, our artistic ability and our supreme intellect,” said Blumenschine.

Adam Habib, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Witswatersrand, hailed the assembly of the full skeleton. “This is a landmark achievement for the global scientific community and South Africa’s heritage,” said Habib. “It is through important discoveries like Little Foot that we obtain a glimpse into our past which helps us to better understand our common humanity.”

3.6-million-year-old human skeleton found, shocking scientists

- Thread starter

- #38

Light shed on how humans populated Americas...

Alaskan 'sunrise' girl sheds light on how humans populated Americas

January 3, 2018 | WASHINGTON - Ancient DNA extracted from the skull of a six-week-old baby girl whose 11,500-year-old remains were unearthed in a burial pit in central Alaska is helping scientists resolve long-standing controversies about how humans first populated the Americas.

Alaskan 'sunrise' girl sheds light on how humans populated Americas

January 3, 2018 | WASHINGTON - Ancient DNA extracted from the skull of a six-week-old baby girl whose 11,500-year-old remains were unearthed in a burial pit in central Alaska is helping scientists resolve long-standing controversies about how humans first populated the Americas.

Scientists said on Wednesday a study of her genome indicated there was just a single wave of migration into the Americas across a land bridge, now submerged, that spanned the Bering Strait and connected Siberia to Alaska during the Ice Age. The infant -- named “sunrise girl-child” (Xach‘itee‘aanenh T‘eede Gaay) using the local indigenous language -- belonged to a previously unknown Native American population that descended from those intrepid migrants, the researchers added. “The study provides the first direct genomic evidence that all Native American ancestry can be traced back to the same source population during the last Ice Age,” University of Alaska Fairbanks archaeologist Ben Potter said.

The remains of the infant -- part of a hunter-gatherer culture that hunted bison, elk, hare, squirrels and birds and caught salmon -- were unearthed in 2013 at a prehistoric encampment in Alaska’s Tanana River Valley about 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Fairbanks. Our species first arose in Africa roughly 300,000 years ago, and later spread around the world. The researchers studied the baby’s genome and genetic data covering other populations to unravel how and when the Americas were first populated. A single ancestral Native American group split from East Asians about 36,000 year ago and thousands of years later crossed the land bridge, they said. This founding group diverged into two lineages about 20,000 years ago.

The first lineage trekked south of the huge ice caps that covered much of North America between 20,000 and 15,000 years ago, spreading throughout North and South America and becoming the ancestors of today’s Native Americans. The second was the newly identified population called Ancient Beringians who included the infant. They eventually disappeared, perhaps absorbed into another population that later inhabited Alaska.

Some scientists previously hypothesized about multiple migratory waves over the land bridge as recent as 14,000 years ago. The girl was found alongside remains of an even-younger female infant, possibly a first cousin, whose genome the researchers could not sequence. Both were covered in red ochre and surrounded by decorated antler tools. “Even the one that got sequenced was a huge challenge due to poor DNA preservation,” said Eske Willerslev, director of the University of Copenhagen’s Centre for GeoGenetics. The research was published in the journal Nature.

Alaskan 'sunrise' girl sheds light on how humans populated Americas

- Thread starter

- #39

Kinda looks like Uncle Ferd's g/f...

This ancient teenager is the first known person with parents of two different species

Aug 23, 2018 - A new ancient DNA study published in Nature Wednesday reports the first known person to have had parents of two different species. The studied remains belonged to a girl who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

See also:

Mixed-species DNA casts new light on early humans

Fri, Aug 24, 2018 - Denny was an inter-species lovechild.

This ancient teenager is the first known person with parents of two different species

Aug 23, 2018 - A new ancient DNA study published in Nature Wednesday reports the first known person to have had parents of two different species. The studied remains belonged to a girl who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) lived throughout Europe and Western Asia until around 30,000 years ago. This species lived in several different ecological zones, survived three glacial periods, and were excellent hunters and tool-makers. Denisovans (Homo sapiens denisova), on the other hand, we know very little about. Thus far they have only been found in Denisova Cave in Sibera as tiny bone fragments. We don’t yet know what they looked like – nor exactly what they were capable of.

Neanderthal, Denisovans, and modern humans all shared a common ancestor more than 400,000 years ago.

Is this what Denisova 11’s mother looked like? A museum model of a Neanderthal woman.

Found in Denisova Cave, this child — known as “Denisova 11” — was at least 13 years of age at the time of her death. Analysis of a piece of her bone found that the girl died more than 50,000 years ago. This discovery occurred through ancient DNA analysis, whereby a small piece of the teenager’s bone was pulverised, the DNA extracted, and then sequenced. The sequence was then compared to previously analysed samples from Neanderthals, modern humans, and Denisovans. Her genetic traits could only be explained if her mother was a Neanderthal and her father was a Denisovan. Denisova 11 was a first generation Neanderthal-Denisovan woman – perhaps we could call her a “Neandersovan”?

Neighbours of modern humans

Neanderthals and Denisovans inhabited Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago when they were replaced by modern humans (Homo sapiens). But before this replacement occurred, there appears to have been a fair bit of mingling going on whenever the different groups met. Indeed, the ancestors of modern-day Oceanians and Asians contain Denisovan DNA, while present-day non-Africans contain 2-4% Neanderthal DNA.

More mobile than we thought

The DNA of this girl — Denisova 11 — also suggests that there was some quite significant movement of Neanderthal groups between Western Europe and the East. Analysis of her DNA found that rather than being more closely related to a Neanderthal who lived in her home cave sometime prior to her birth, she instead showed more connections to those recovered in Western Europe. This finding is interesting because most archaeological evidenceindicates that Neanderthals — unlike modern humans — were not interested in long-distance movement. They don’t seem to have moved much beyond relatively constrained territories which provided everything they needed for day-to-day life.

MORE

See also:

Mixed-species DNA casts new light on early humans

Fri, Aug 24, 2018 - Denny was an inter-species lovechild.

Her mother was a Neanderthal, but her father was Denisovan, a distinct species of primitive human that also roamed the Eurasian continent 50,000 years ago, scientists reported in Nature on Wednesday. Nicknamed by Oxford University scientists, Denisova 11 — her official name — was at least 13 when she died for reasons unknown. “There was earlier evidence of interbreeding between different hominin, or early human, groups,” said lead author Vivian Slon, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “But this is the first time that we have found a direct, first-generation offspring.” Denny’s surprising pedigree was unlocked from a bone fragment unearthed in 2012 by Russian archeologists at the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia.

Analysis of the bone’s DNA left no doubt: The chromosomes were a 50-50 mix of Neanderthal and Denisovan, two distinct species of early humans that split apart between 400,000 to 500,000 years ago. “I initially thought that they must have screwed up in the lab,” said senior author and Max Planck Institute professor Svante Paabo, who identified the first Denisovan a decade ago at the same site. Worldwide, fewer than two dozen early human genomes from before 40,000 years ago — Neanderthal, Denisovan and Homo sapiens — have been sequenced, and the chances of stumbling on a half-and-half hybrid seemed vanishingly small. Or not. “The very fact that we found this individual of mixed Neanderthal and Denisovan origins suggests that they interbred much more often than we thought,” said Slon.

A 40,000-year-old Homo sapiens with a Neanderthal ancestor a few generations back, recently found in Romania, also bolsters this notion, but the most compelling evidence that inter-species hanky-panky in Late Pleistocene Eurasia might not have been that rare lies in the genes of contemporary humans. About 2 percent of DNA in non-Africans across the globe today originates with Neanderthals, earlier studies have shown. Denisovan remnants are also widespread, although less evenly. “We find traces of Denisovan DNA — less than 1 percent — everywhere in Asia and among native Americans,” Paabo said. “Aboriginal Australians and people in Papua New Guinea have about 5 percent.” Taken together, these facts support a novel answer to the hotly debated question of why Neanderthals — who had successfully spread across parts of western and central Europe — disappeared about 40,000 years ago.

What if our species — arriving in waves from Africa — overwhelmed Neanderthals, and perhaps Denisovans, with affection rather than aggression? “Part of the story of these groups is that they may simply have been absorbed by modern populations,” Paabo said. Recent research showing that Neanderthals were not knuckle-dragging brutes makes this scenario all the more plausible. Far less is known about Denisovans, but they might have suffered a similar fate. Paabo established their existence with an incomplete finger bone and two molars dated to about 80,000 years ago. Among their genetic legacy to some modern humans is a variant of the gene EPAS1, which makes it easier for the body to access oxygen by regulating the production of hemoglobin, a 2014 study said. Nearly 90 percent of Tibetans have this precious variant, compared with only 9 percent of Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic group in China.

Mixed-species DNA casts new light on early humans - Taipei Times

DNA testing has a lot of problems, and shouldn't be blindly trusted. And, old bones shouldn't be referred to as 'human ancestors', since they aren't, they're extinct species of apes or some other life form, not humans. Calling them 'human ancestors' is speculation, not science.

Outside of that, these are cool articles, especially the latest dated ones.

Outside of that, these are cool articles, especially the latest dated ones.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 212

- Replies

- 60

- Views

- 980

- Replies

- 842

- Views

- 6K

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 537

Latest Discussions

- Replies

- 4K

- Views

- 83K

- Replies

- 111

- Views

- 434

- Replies

- 105

- Views

- 581

- Replies

- 16

- Views

- 72

- Replies

- 35

- Views

- 187

Forum List

-

-

-

-

-

Political Satire 8032

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

ObamaCare 781

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Member Usernotes 468

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-