Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

No More Russian Adoption

- Thread starter Unkotare

- Start date

Protest in Russia to anti-America adoption ban...

Thousands march to protest Russia's adoption ban

Jan 13,`13 MOSCOW (AP) -- Thousands of people marched through Moscow on Sunday to protest Russia's new law banning Americans from adopting Russian children, a far bigger number than expected in a sign that outrage over the ban has breathed some life into the dispirited anti-Kremlin opposition movement.

Thousands march to protest Russia's adoption ban

Jan 13,`13 MOSCOW (AP) -- Thousands of people marched through Moscow on Sunday to protest Russia's new law banning Americans from adopting Russian children, a far bigger number than expected in a sign that outrage over the ban has breathed some life into the dispirited anti-Kremlin opposition movement.

Shouting "shame on the scum," protesters carried posters of President Vladimir Putin and members of Russia's parliament who overwhelmingly voted for the law last month. Up to 20,000 took part in the demonstration on a frigid, gray afternoon. The adoption ban has stoked the anger of the same middle-class, urban professionals who swelled the protest ranks last winter, when more than 100,000 people turned out for rallies to demand free elections and an end to Putin's 12 years in power. Since Putin began a third presidential term in May, the protests have flagged as the opposition leaders have struggled to provide direction and capitalize on the broad discontent.

Opponents of the adoption ban argue it victimizes children to make a political point. Eager to take advantage of this anger, the anti-Kremlin opposition has played the ban as further evidence that Putin and his parliament have lost the moral right to rule Russia. The Kremlin, however, has used the adoption controversy to further its efforts to discredit the opposition as unpatriotic and in the pay of the Americans.

Sunday's march may prove only a blip on what promises to be a long road for the protest movement, especially in the face of Kremlin efforts to stifle dissent. But it was a reunion of what has become known as Moscow's creative class, whose sarcastic wit was once again on display on Sunday. "Parliament deputies to orphanages, Putin to an old people's home," read one poster. Another showed Putin with the words "For a Russia without Herod." Putin's critics have likened him to King Herod, who ruled at the time of Jesus Christ's birth and who the Bible says ordered the massacre of Jewish children to avoid being supplanted by the newborn king of the Jews.

Russia's adoption ban was retaliation for a new U.S. law targeting Russians accused of human rights abuses. It also addresses long-brewing resentment in Russia over the 60,000 Russian children who have been adopted by Americans in the past two decades, 19 of whom have died. Cases of Russian children dying or suffering abuse at the hands of their American adoptive parents have been widely publicized in Russia, and the law banning adoptions was called the Dima Yakovlev bill after a toddler who died in 2008 when he was left in a car for hours in broiling heat. "Yes, there are cases when they are abused and killed, but they are rare," said Sergei Udaltsov, who heads a leftist opposition group. "Concrete measures should be taken (to punish those responsible), but our government decided to act differently and sacrifice children's fates for its political ambitions."

MORE

- Feb 12, 2007

- 59,384

- 24,018

- 2,290

Incomplete statistics are misleading - hardly surprising considering the source.

Russia's health ministry predicted on Wednesday that the birth rate in Russia would equal the mortality rate by 2011.

"By 2011 the mortality rate should be equal to the birth rate," Social Development and Health Minister Tatyana Golikova said.

In the first eleven months of 2007 the mortality rate in Russia was 14.7 deaths per 1,000 live births, and 15.3 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2006, the minister said.

The average mortality rate for the 27-member European Union in 2006 was 10.1 deaths per 1,000 live births. The first time in European modern history the death rate exceeded births.

Demographic issues are widely seen as one of the main threats facing modern Russia since market reforms and economic hardship of the 1990s.

Many experts are concerned that Russia will be hit be a demographic crisis in the near future and according to UN predictions, Russia's population, currently at about 142 million, could fall by 30% by the middle of the century.

In October, Russian President Vladimir Putin approved a set of targets to improve the country's demographic policy to 2025. The proposals are designed to lower the national mortality rate, raise birth rates, improve national health and regulate immigration.

Russia's birth, mortality rates to equal by 2011 - ministry | Russia | RIA Novosti

In addition, the fertility rate for adult women remains far below the 2.1 lives births/woman required to maintain a stable population.

Russia's health ministry predicted on Wednesday that the birth rate in Russia would equal the mortality rate by 2011.

"By 2011 the mortality rate should be equal to the birth rate," Social Development and Health Minister Tatyana Golikova said.

In the first eleven months of 2007 the mortality rate in Russia was 14.7 deaths per 1,000 live births, and 15.3 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2006, the minister said.

The average mortality rate for the 27-member European Union in 2006 was 10.1 deaths per 1,000 live births. The first time in European modern history the death rate exceeded births.

Demographic issues are widely seen as one of the main threats facing modern Russia since market reforms and economic hardship of the 1990s.

Many experts are concerned that Russia will be hit be a demographic crisis in the near future and according to UN predictions, Russia's population, currently at about 142 million, could fall by 30% by the middle of the century.

In October, Russian President Vladimir Putin approved a set of targets to improve the country's demographic policy to 2025. The proposals are designed to lower the national mortality rate, raise birth rates, improve national health and regulate immigration.

Russia's birth, mortality rates to equal by 2011 - ministry | Russia | RIA Novosti

In addition, the fertility rate for adult women remains far below the 2.1 lives births/woman required to maintain a stable population.

I know a couple who adopted a Russian boy a few years ago and they had a tough time with him. Russians are notoriously heavy drinkers and apparently fetal alcohol syndrome is so common in Russia that it has reached epidemic proportions. It's possible that the Russian government is concerned that Americans who adopted Russian kids will pool their information and the word will get out.

This is another failure of obama's foreign policy. How is that "reset" button working out for ya Bammy?

Banning US adoptions isn't because the US complained about Russia's human rights abuses. It's because of the Magnitsky Act. A punishment of financial sanctions levied against Russian interests in the US because of purely internal acts in Russia. The alleged human rights abuses weren't fooling anyone. The US wanted financial sanctions! This was just a good excuse. Then, like the street thug he is, obama thought that Russia would just take it. Maybe complain to the UN. Victims of thuggishness have no right to take action, just complain.

obama is simply being treated the way he treats everyone else. He's king of the US, not king of the world, although he thinks he is.

Banning US adoptions isn't because the US complained about Russia's human rights abuses. It's because of the Magnitsky Act. A punishment of financial sanctions levied against Russian interests in the US because of purely internal acts in Russia. The alleged human rights abuses weren't fooling anyone. The US wanted financial sanctions! This was just a good excuse. Then, like the street thug he is, obama thought that Russia would just take it. Maybe complain to the UN. Victims of thuggishness have no right to take action, just complain.

obama is simply being treated the way he treats everyone else. He's king of the US, not king of the world, although he thinks he is.

The boy's death has stoked Russian anger about the treatment of adoptees in the United States...

Russia investigates 'murder' of Max Shatto, US adoptee

19 February 2013 - Russia's top investigative body has opened a murder inquiry after a three-year-old adoptee died in the US.

See also:

Texas Authorities Investigate Death of Adopted Russian Child

February 19, 2013 — Authorities in Ector County, in west Texas, are investigating the death of a three-year-old boy who was born in Russia and adopted by a US couple living in that area. A medical examiner raised questions about possible abuse after a preliminary inspection of the boy's body, which is now undergoing an autopsy.

Russia investigates 'murder' of Max Shatto, US adoptee

19 February 2013 - Russia's top investigative body has opened a murder inquiry after a three-year-old adoptee died in the US.

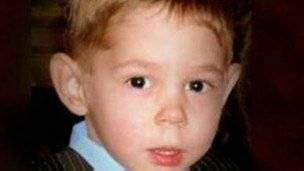

Max Shatto - whose Russian name is Maxim Kuzmin - died on 21 January. Texas officials say they are still investigating the death, and no arrests have been made. The case comes at a sensitive time, with Russia having just banned US adoptions because of previous deaths. Russian officials have alleged the child suffered "inhuman abuse". Russia's equivalent of the FBI, the Investigative Committee, has opened a murder investigation and says it will ensure that the "murderers of the Russian child are severely punished". Max Shatto and his younger brother Kristopher were adopted from an orphanage in north-west Russia last year by Alan and Laura Shatto, who live in Gardendale, Texas.

He died on 21 January, less than two weeks after his third birthday. "I would like to draw your attention to another case of inhuman abuse of a Russian child by US adoptive parents," Konstantin Dolgov, the Russian Foreign Ministry's special representative for human rights, said in a statement. Mr Dolgov said the child had suffered injuries that "could only be caused by strong blows", and alleged that the boy's adoptive parents had given him a strong anti-psychotic drug mainly used to treat schizophrenic adults. Texas Child Protection Services confirmed it had received allegations of physical abuse and neglect and was investigating, but had not yet determined whether the allegations were true.

'Singing with the angels'

The Ector County Sheriff's Office is also investigating, but says it is awaiting autopsy results. The US state department said it would help Russian officials make contact with the appropriate authorities in Texas, and that it "took very seriously the welfare of children, particularly children who have been adopted from other countries".

Max's adoptive parents have said they will not comment. A tribute to Max was published on the website of a funeral home which handled arrangements for his funeral: "Max, you were not with us long enough to leave fingerprints on the walls but you left fingerprints upon our hearts. When we get to Heaven, we know we will hear your sweet voice singing with the angels. We love you and will always miss you." The boy's death came just three weeks after the Russian parliament, the Duma, enacted legislation ending all adoptions of Russian orphans by Americans. The move was criticised by the United States and by the opposition in Moscow. Russian politicians have been quick to seize on Max Shatto's death as a clear justification for their hardline stance, says the BBC's Daniel Sandford in Moscow.

BBC News - Russia investigates 'murder' of Max Shatto, US adoptee

See also:

Texas Authorities Investigate Death of Adopted Russian Child

February 19, 2013 — Authorities in Ector County, in west Texas, are investigating the death of a three-year-old boy who was born in Russia and adopted by a US couple living in that area. A medical examiner raised questions about possible abuse after a preliminary inspection of the boy's body, which is now undergoing an autopsy.

State and local authorities are proceeding with an investigation into the death of three-year-old Max Shatto on January 21 in Odessa, Texas, but they still have no determination of cause and have not made any arrests. Ector County Sheriff's Department Sergeant Gary Duesler says several local agencies became involved in the case very quickly. “The Medical Examiners office and, of course, our office is involved in it, Child Protective Services because it did not look like a natural death to us," said Duesler. "So we sent the body off for an autopsy in Tarrant County and we are currently waiting for the results to come back on that.”

Duesler says Odessa is too small to have its own autopsy facility so such cases are often handled by a hospital in a larger city like Dallas. He says investigators have spoken to the family, but have not filed any charges yet. “We are starting to try to put the pieces of the puzzle together. It is an ongoing investigation and we are basically in limbo until we get results back from the autopsy," he said. Duesler says the sheriff's department is in contact with the Russian embassy in Washington and with US Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana. Senator Landrieu recently headed a group of ten US senators at a meeting with officials at the Russian embassy about the ban on US adoptions Russia imposed late last year.

At the US State Department Tuesday, spokeswoman Victoria Nuland described the death of Max Shatto as a tragedy and said US officials are keeping in touch with both the Russian embassy and the Russian consulate in Houston. But Nuland cautioned that it is still too early to say what happened to the adopted boy. “Nobody should jump to any conclusions about how this child died until Texas authorities have had a chance to investigate," said Nuland.

The death of the boy in west Texas has aroused Russian critics of US child adoptions who say not enough is being done to protect adopted children from abusive or negligent parents. Russian officials expressed outrage in 2008 when an adopted toddler named Dima Yakovlev died in Virginia after being left alone in a closed car in intense heat. Max Shatto, whose birth name was Maxim Kuzmin, came from the same orphanage in Russia. Texas officials say his two-year-old brother remains in the home of the adoptive parents, Alan and Laura Shatto, while the investigation proceeds.

http://www.voanews.com/content/tgex...e-death-of-adopted-russian-child/1606928.html

Last edited:

Max Shatto case becomes international incident...

Toddler death stirs Russian polemic over US adoption

26 February 2013 - Tuesday's meeting between the new US Secretary of State John Kerry and the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov comes at the lowest point in the countries' relationship since President Obama first took office.

Toddler death stirs Russian polemic over US adoption

26 February 2013 - Tuesday's meeting between the new US Secretary of State John Kerry and the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov comes at the lowest point in the countries' relationship since President Obama first took office.

The "reset" was knocked badly off course by disagreements over the conflicts in Libya and Syria. Then, during last year's protests, Russia accused America of interfering in its domestic politics. This ended with USAID being kicked out the country. December's Sergei Magnitsky Act that allows Russian officials to be excluded from the US on human rights grounds only made things worse, and Moscow's response was to end all adoptions of Russian children by American parents. Then last week, just seven weeks after that controversial ban was enacted came the tragic news of the death of Max Shatto, previously known as Maksim Kuzmin.

The three-year-old boy and his two-year-old brother Kristopher Shatto (previously known as Kirill Kuzmin) had only arrived in the US in October to live with their new parents Laura and Alan Shatto. But on 21 January, Max Shatto was rushed to hospital where he was pronounced dead. How he died is not yet clear. Sondra Woolf, an investigator at the Ector County Medical Examiner said: "There was some bruising just in various places. Whether they had anything to do with his cause of death we don't know. We won't know until we get the autopsy report back."

Max Shatto (l), seen here with his brother Kristopher, died barely three months after arriving in the US

Media firestorm

But the Russian reaction was very different. The Children's Commissioner Pavel Astakhov broke the news on Twitter. "An adoptive mother has killed a three-year-old Russian child in the state of Texas. The murder occurred at the end of January," he wrote. That unleashed a firestorm in the Russian media and the parliament, the Duma. Deputies lined up to use Max Shatto's death to justify the ban on US adoptions of Russian children. "Why should we send our children to certain death?" asked Svetlana Orlova, the deputy chair of the Russian upper chamber, the Federation Council.

But at the children's home that Maksim Kuzmin was adopted from, we found a very different reaction. "The ban on American adoptions will mostly hit children with serious health problems," the chief doctor, Natalia Vishnevskaya, said. "Russian adoptive parents are afraid of taking these kinds of children. And in our children's home there are practically no kids who are absolutely healthy." The Pechory Baby Home has seen a similar tragedy before. Dima Yakovlev - a 21-month-old toddler who had left the home only a few months earlier - died of heatstroke after being accidentally left in a car by his adoptive father in Virginia. But still Natalia Vishnevskaya is in favour of US adoptions. "These tragic events should not prevent our children from being adopted to any country," she said, "and let me stress any country."

'Sensational exploitations'

Cover-up!...

Max Shatto Russia-US adoption death ruled an accident

1 March 2013 : The investigation into Max Shatto's death is still continuing, prosecutors say

Max Shatto Russia-US adoption death ruled an accident

1 March 2013 : The investigation into Max Shatto's death is still continuing, prosecutors say

The death in Texas of an adopted three-year-old Russian boy has been ruled an accident, reports quoting US officials say amid ongoing tensions over the case between the US and Moscow. Max Shatto died accidentally after he hit himself and tore an artery, media citing a coroner's report said. The child died in January. He was adopted from a Russian orphanage. Russian parliamentarians have regularly used the death to justify a recent ban on adoptions to America. A senior Russian official, Pavel Astakhov, sparked controversy last month by alleging that the boy, born Maxim Kuzmin, was murdered by his adoptive parents.

But four doctors who reviewed the autopsy results said the adoptive parents of Max Shatto had done nothing wrong, CBS 7 news reported. The medical examiner in Ector County, Texas said Max's death was not intentional, according to Sheriff Mark Donaldson and prosecutor Bobby Bland. Autopsy results showed that bruises on several parts of the boy's body were self-inflicted and it was reported that the child had a mental disorder which had caused him to hurt himself. "I had four doctors agree that this is the result of an accident," Mr Bland said. "We have to take that as fact."

However, the investigation over what happened is still continuing, officials added. The prosecutor said that he would see whether to pursue charges such as negligent supervision or injury to a child by omission, after the full results of the investigation were available. The boy was reportedly found unresponsive outside the family home in Gardendale, Texas on 21 January. He had been adopted, along with his half-brother Kristopher, last autumn.

The boy's death came just three weeks after the Russian parliament, the Duma, enacted legislation ending all adoptions of Russian orphans by Americans - a move criticised by the US and by the opposition in Moscow. The adoption ban has been viewed as retaliation for a law passed in the US that would stop Russian officials suspected of human right violations from coming to the US. Russian authorities have said they are pursuing their own investigation into the death.

BBC News - Max Shatto Russia-US adoption death ruled an accident

No charges in Max Shatto death...

Max Shatto: Texas prosecutor declines charges in death

18 March 2013 - Doctors said bruises found on Max's dead body were probably self-inflicted, not the result of abuse

Max Shatto: Texas prosecutor declines charges in death

18 March 2013 - Doctors said bruises found on Max's dead body were probably self-inflicted, not the result of abuse

Prosecutors in Texas say they will not charge a couple whose adopted Russian son's death was ruled an accident. Max Shatto, adopted from a Russian orphanage, died age 3 in January, soon after Russia banned all US adoptions. A grand jury had found insufficient evidence to charge Alan and Laura Shatto, a prosecutor said. The case sparked outrage in Russia, where authorities have launched their own investigation and demanded the Shattos face charges. Texas doctors who examined the boy ruled his death had been an accident and that bruises on his body were self-inflicted.

According to preliminary results of a post-mortem examination released this month, the child died accidentally from a torn artery in his abdomen and had bruises consistent with injuring himself. No drugs or medicines had been found in his body and the coroner said he had had a mental disorder that caused him to hurt himself. Earlier this month, more than 10,000 people marched in Moscow to demanded a halt to all foreign adoptions of Russian children. Max Shatto, born Maksim Kuzmin, and his younger brother Kristopher were adopted from an orphanage in north-west Russia last year by the Shattos, who live in Gardendale, Texas.

Murder allegation

Laura Shatto said she had found him unconscious outside the family's home and he died later in hospital. When he died, Russia's children's commissioner Pavel Astakhov alleged he had been murdered by his adoptive mother. But the Shattos' lawyer said the toddler had suffered from behavioural issues and occasionally butted his head on objects or other people.

Kristopher still lives with the Shattos. In December, the Russian government banned adoptions of Russian orphans by Americans. Correspondents say Russia did so in retaliation for the US passing a law allowing Russian officials suspected of human rights abuses to be banned from the US.

BBC News - Max Shatto: Texas prosecutor declines charges in death

t_polkow

Rookie

- Banned

- #15

Fertility Decline and Recent Changes in Russia

It was in late 1991 that, for the first time in the postwar history of the Russian population, the number of deaths exceeded that of births. In 1992 the negative natural change amounted to 219,800, or 1.5 per 1,000. An even greater decrease was recorded in 1993, with a 750,300 natural decrease in population, or 5.1 per 1,000. This natural decrease was larger than the positive change due to net immigration and resulted in a total population decrease by 30,900 in 1992 and by 307,600 in 1993.

Russia has entered the stage of negative population change.

Fertility Decline and Recent Changes in Russia: On the Threshold of the Second Demographic Transition | RAND

t_polkow

Rookie

- Banned

- #16

Fertility Decline and Recent Changes in Russia

It was in late 1991 that, for the first time in the postwar history of the Russian population, the number of deaths exceeded that of births. In 1992 the negative natural change amounted to 219,800, or 1.5 per 1,000. An even greater decrease was recorded in 1993, with a 750,300 natural decrease in population, or 5.1 per 1,000. This natural decrease was larger than the positive change due to net immigration and resulted in a total population decrease by 30,900 in 1992 and by 307,600 in 1993.

Russia has entered the stage of negative population change.

Fertility Decline and Recent Changes in Russia: On the Threshold of the Second Demographic Transition | RAND

The single greatest cause of recent population decline in Russia is a fall in the number of births (Figure 1). From 1987 to 1999, the annual number of births in Russia declined from 2.5 million to 1.2 million.

The fall in Russian fertility, however, long predates the final years of the Soviet Union. At the end of the 19th century, Russian women bore, on average, around 7 children; by 2000, this average had fallen to 1.2. Nor have declining fertility rates been unique to Russia. Since the 1950s, fertility rates have fallen throughout Europe and North America, and, as in Russia, they are now below replacement level, or 2.1 children per woman, in a number of industrialized countries (Figure 2). In Russia in 2000, there were 1,266,000 births and 2,225,000 deaths.

The Current State of Health in Russia and the Former Soviet Union

t_polkow

Rookie

- Banned

- #17

Ain't Capitalism grand?

A consortium headed by the World Health Organization estimated that for 2005 a woman’s risk of death in childbirth in Russia was over six times higher than in Germany or Switzerland. Moreover, mortality levels for women in their twenties (the decade in which childbearing is concentrated in contemporary Russia) have been rising, not falling, in recent decades.

But Russia’s low fertility patterns are not due to any extraordinary inability of Russian women to conceive, but rather to the strong and growing tendency among childbearing women to have no more than two children—and perhaps increasingly not more than one. The new evident limits on family size in Russia, in turn, suggest a sea change in the country’s norms concerning family formation.

In 1980, fewer than one Russian newborn in nine was reportedly born out of wedlock. By 2005, the country’s illegitimacy ratio was approaching 30 percent—almost a tripling in just twenty years. Marriage is not only less common in Russia today than in the recent past; it is also markedly less stable. In 2005, the total number of marriages celebrated in Russia was down by nearly one-fourth from 1980 (a fairly typical Brezhnev-period year for marriages). On the other hand, the total number of divorces recognized in Russia has been on an erratic rise over the past generation, from under 400 divorces per 1,000 marriages in 1980 to a peak of over 800 in 2002.

In 1990, the end of the Gorbachev era, marriage was still the norm, and while divorce was very common, a distinct majority of Russian Federation women (60 percent) could expect to have entered into a first marriage and still remain in that marriage by age 50. A few years later, in 1996, the picture was already radically different: barely a third of Russia’s women (34 percent) were getting married and staying in that same marriage until age 50.

Since the end of the Soviet era, young women in Russia are opting for cohabitation before and, to a striking extent, instead of marriage. In the early 1980s, about 15 percent of women had been in consensual unions by age 25; twenty years later, the proportion was 45 percent. Many fewer of those once-cohabiting young women, moreover, seem to be moving into marital unions nowadays. Whereas roughly a generation earlier, fully half of cohabiters were married within a year, today less than a third are.

Is Russia’s post-Communist plunge in births the consequence of a “demographic shock,” or the result of what some Russian experts call a “quiet revolution” in patterns of family formation? At the moment, it is possible to see elements of both in the Russian Federation’s unfolding fertility trends. Demographic shocks tend by nature to be transient; demographic transitions or “revolutions,” considerably less so. But this much is clear: to date, no European society that has embarked upon the same demographic transition as Russia’s—declining marriage rates with rising divorce; the spread of cohabitation as alternative to marriage; delayed age at marriage and sub-replacement fertility regimens—has reverted to more “traditional” family patterns and higher levels of completed family size. There is no reason to think that in Russia it will be any different.

There are many ramifications of the dramatic decline in population in Russia, but three in particular bear heavily on the country’s prospective development and national security.

First, when Western European nations reached the level of 30 percent illegitimate births that Russia has now attained, their levels of per capita output were all dramatically higher—three times higher in France, Austria, and Britain, and higher than that in countries such as Germany, Ireland, and the Netherlands.

This means that Russia’s mothers and their children will be afforded far fewer of the social protections that their counterparts could count on in Western Europe’s more generous welfare states.

A second and related point pertains to “investment” in children. According to prevailing tenets of Western economic thought, a decline in fertility—to the extent that it occurs under conditions of orderly progress, and as a consequence of parental volition—should mean a better material environment for newborns and children because a shift to smaller desired family size, all else being equal, signifies an increase in parents’ expected commitments to each child’s education, nutrition, health care, and the like.

Yet in post-Communist Russia, there are unambiguous indications of a worsening of social well-being for a significant proportion of the country’s children—in effect, a disinvestment in children in the face of a pronounced downward shift in national fertility patterns.

School enrollment is sharply lower for primary-school-age children—99 percent in 1991 versus 91 percent in 2004. And the number of abandoned children is sharply higher. According to official statistics, as of 2004 over 400,000 Russian children below 18 years of age were in “residential care.” This means that roughly 1 child in 70 was in a children’s home, orphanage, or state boarding school. Russia is also home to a large and possibly growing contingent of street children whose numbers could well exceed those under institutional care. According to Human Rights Watch, over 100,000 children in Russia have been abandoned by their parents each year since 1996. If accurate, this number, compared to the annual tally of births for the Russian Federation, which averaged about 1.4 million a year for the 1996–2007 period, would suggest that in excess of 7 percent of Russia’s children are being discarded by their parents in this new era of steep sub-replacement fertility.

A third implication of the past decade and a half of sharply lower birth levels in Russia will be a drop-off in the country’s working-age population, and an acceleration of the tempo of population aging in the period immediately ahead. Barring only a steady and massive in-migration, Russia’s potential labor pool will shrink markedly over the coming decade and a half and continue to diminish thereafter.

In addition to its daunting fertility decline, Russia’s public health losses today are of a scale akin to what might be expected from a devastating war. Since the end of the Communist era, in fact, “excess mortality” has cost Russia hundreds of thousands of lives every year.

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed an increase in mortality rates for key elements of the Soviet population. But Russia’s health patterns did not correct course with the collapse of the USSR, as many experts assumed they would. In fact, in the first decade and a half of its post-Communist history the country’s health conditions actually became worse. Life expectancy in the Russian Federation is actually lower today than it was a half century ago in the late 1950s. In fact, the country has pioneered a unique new profile of mass debilitation and foreshortened life previously unknown in all of human history.

Like the urbanized and literate societies in Western Europe, North America, and elsewhere, the overwhelming majority of deaths in Russia today accrue from chronic rather than infectious diseases: heart disease, cancers, strokes, and the like. But in the rest of the developed world, death rates from these chronic diseases are low, relatively stable, and declining regularly over time. In the Russian Federation, by contrast, overall mortality levels are high, manifestly unstable, and rising.

The single clearest and most comprehensible summary measure of a population’s mortality prospects is its estimated expectation of life at birth. Russia’s trends in the late 1950s and early 1960s were rising briskly. In the five years between 1959 and 1964, for instance, life expectancy increased by more than two years. But then, inexplicably, overall health progress in Russia came to a sudden and spectacular halt. Over that 18-year period that roughly coincides with the Brezhnev era, Russia’s life expectancy not only stagnated, but actually fell by about a year and a half.

These losses were recovered during the Gorbachev period, but even at its pinnacle in 1986 and 1987, overall life expectancy for Russia was only marginally higher than it had been in 1964, never actually managing to cross the symbolic 70-year threshold. With the end of Communism, moreover, life expectancy went into erratic decline, plummeting a frightful four years between 1992 and 1994, recovering somewhat through 1998, but then again spiraling downward. In 2006—the most recent year for which we have such data—overall Russian life expectancy at birth was over three years lower than it had been in 1964.

The situation for Russian males has been particularly woeful. In the immediate postwar era, life expectancy for men was somewhat lower than in other developed countries—but this differential might partly be attributed to the special hardships of World War II and the evils of Stalinism. By the early 1960s, the male life expectancy gap between Russia and the more developed regions narrowed somewhat—but then life expectancy for Russian men entered into a prolonged and agonizing decline, while continued improvements characterized most of the rest of the world. By 2005, male life expectancy at birth was fully fifteen years lower in the Russian Federation than in Western Europe. It was also five years below the global average for male life expectancy, and three years below the average for the less developed regions (whose levels it had exceeded, in the early 1950s, by fully two decades). Put another way, male life expectancy in 2006 was about two and a half years lower under Putin than it had been in 1959, under Khrushchev.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau International Data Base for 2007, Russia ranked 164 out of 226 globally in overall life expectancy. Russia is below Bolivia, South America’s poorest (and least healthy) country and lower than Iraq and India, but somewhat higher than Pakistan. For females, the Russian Federation life expectancy will not be as high as in Nicaragua, Morocco, or Egypt. For males, it will be in the same league as that of Cambodia, Ghana, and Eritrea.

In the face of today’s exceptionally elevated mortality levels for Russia’s young adults, it is no wonder that an unspecified proportion of the country’s would-be mothers and fathers respond by opting for fewer offspring than they would otherwise desire. To a degree not generally appreciated, Russia’s current fertility crisis is a consequence of its mortality crisis.

How did Russia’s mortality level, which was nearly 38 percent higher than Western Europe’s in 1980, skyrocket to an astonishing 135 percent higher in 2006? What role did communicable and infectious disease play in this fateful health regression and mortality deterioration?

By any reading, the situation in Russia today sounds awful. The Russian Federation is afflicted with a serious HIV/AIDS epidemic; according to UNAIDS, as of 2008 somewhere around 1 million Russians were living with the virus. (Russia’s HIV nexus appears to be closely associated with a burgeoning phenomenon of local drug use, with sex trafficking and other forms of prostitution or “commercial sex,” and with other practices and mores relating to extramarital sex.) Russia also faces a related and evidently growing burden of tuberculosis. As of 2008, according to World Health Organization estimates, Russia was experiencing about 150,000 new TB infections a year. To make matters worse, almost half of Russia’s treated tubercular cases over the past decade have been the variant known as extreme drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB).

Yet, dismaying as these statistics are, the picture looks even worse when we consider cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality trends.

By the late 1960s, the epidemic upsurge of CVD mortality in Western industrial societies that immediately followed World War II had peaked. From the mid-1970s onward, age-standardized death rates from diseases of the circulatory system steadily declined in Western Europe. In Russia, by stark contrast, CVD mortality in 1980 was well over 50 percent higher than it had been in “old” EU states as of 1970, and the Russian population may well have been suffering the very highest incidence of mortality from diseases of the circulatory system that had ever been visited on a national population in the entire course of human history.

Over the subsequent decades, unfortunately, the level of CVD mortality in the Russian Federation veered even further upward. By 2006, Russia’s CVD mortality rate, standardizing for population structure, was an almost unbelievable 3.8 times higher than the population-weighted level reported for Western Europe.

Scarcely less alarming was Russia’s mortality rate from “external causes”—non-communicable deaths from injuries of various origins. The tale here is broadly similar to the story of CVD: impossibly high levels of death in a society that otherwise does not exhibit signs of backwardness.

In Western Europe, age-standardized mortality from injury and poisoning, as tabulated by the World Health Organization, fell by almost half between 1970 and 2006. In Russia, on the other hand, deaths from injuries and poisoning, which had been 2.5 times higher than in Western Europe in 1980, were up to 5.3 times higher as of 2006.

A broadly negative relationship was evident between mortality from injuries and per capita income. In other Western countries in 2002, an increase of 10 percent in per capita GDP was associated with a drop of about 2 points in injury deaths per 100,000 population. Yet Russia’s toll of deaths is nearly three times higher than would be predicted by its GDP. No literate and urban society in the modern world faces a risk of deaths from injuries comparable to the one that Russia experiences.

Russia’s patterns of death from injury and violence (by whatever provenance) are so extreme and brutal that they invite comparison only with the most tormented spots on the face of the planet today. The five places estimated to be roughly in the same league as Russia as of 2002 were Angola, Burundi, Congo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. To go by its level of mortality injury alone, Russia looks not like an emerging middle-income market economy at peace, but rather like an impoverished sub-Saharan conflict or post-conflict society.

Taken together, then, deaths from cardiovascular disease and from injuries and poisoning have evidently been the main drivers of modern Russia’s strange upsurge in premature mortality and its broad, prolonged retrogression in public health conditions. One final factor that is intimately associated with both of these causes of mortality is alcohol abuse.

Unlike drinking patterns prevalent in, say, Mediterranean regions—where wine is regarded as an elixir for enhancing conversation over meals and other social gatherings, and where public drunkenness carries an embarrassing stigma—mind-numbing, stupefying binge drinking of hard spirits is an accepted norm in Russia and greatly increases the danger of fatal injury through falls, traffic accidents, violent confrontations, homicide, suicide, and so on. Further, extreme binge drinking (especially of hard spirits) is associated with stress on the cardiovascular system and heightened risk of CVD mortality.

How many Russians are actually drinkers, and how heavily do they actually drink? Officially, Russia classifies some 7 million out of roughly 120 million persons over 15 years of age, or roughly 6 percent of its adult population, as heavy drinkers. But the numbers are surely higher than this. According to data compiled by the World Health Organization, as of 2003 Russia was Europe’s heaviest per capita spirits consumer; its reported hard liquor consumption was over four times as high as Portugal’s, three times that of Germany or Spain, and over two and a half times higher than that of France.

Yet even these numbers may substantially understate hard spirit use in Russia, since the WHO figures follow only the retail sale of hard liquor. But samogon—home-brew, or “moonshine”—is, according to some Russian researchers, a huge component of the country’s overall intake. Professor Alexander Nemstov, perhaps Russia’s leading specialist in this area, argues that Russia’s adult population—women as well as men—puts down the equivalent of a bottle of vodka per week.

From the epidemiological standpoint, local-level studies have offered fairly chilling proof that alcohol is a direct factor in premature mortality. One forensic investigation of blood alcohol content by a medical examiner’s office in a city in the Urals, for example, indicated that over 40 percent of the younger male decedents evaluated had probably been alcohol-impaired or severely intoxicated at the time of death—including one quarter of the deaths from heart disease and over half of those from accidents or injuries. But medical and epidemiological studies have also demonstrated that, in addition to its many deaths from consumption of ordinary alcohol, Russia also suffers a grisly toll from alcohol poisoning, as the country’s drinkers, in their desperate quest for intoxication, down not only sometimes severely impure samogon, but also perfumes, alcohol-based medicines, cleaning solutions, and other deadly liquids. Death rates from such alcohol poisoning appear to be at least one hundred times higher in Russia than the United States—this despite the fact that the retail price in Russia today is lower for a liter of vodka than a liter of milk.

Josef Stalin is said to have coldly joked that one death was a tragedy, while one million deaths was just a statistic. This comment seems to apply to post-Communist Russia as well to Stalin’s own deranged regime. For the better part of a generation, Russia has suffered something akin to wartime population losses during year after year of peacetime political order. In the United Nations Development Program’s annually tabulated “Human Development Index,” which uses health as well as economic data to measure a country’s living standards as they affect quality of life, Russia was number 73 out of 179. A country of virtually universal literacy and quite respectable general educational attainment, with a scientific cadre that mastered nuclear fission over half a century ago and launches orbital spacecraft and interplanetary probes today, finds itself ranked on this metric between Mauritius and Ecuador.

In the modern era, population decline itself need not be a cause for acute economic alarm. Italy, Germany, and Japan are among the societies where signs of incipient population decline are being registered nowadays: all of these are affluent countries, and all can anticipate continuing improvements in their respective levels of prosperity (albeit at a slower tempo than some might prefer). Depopulation with Russian characteristics—population decline powered by an explosive upsurge of illness and mortality—is altogether more forbidding in its economic implications, not only forcing down popular well-being today, but also placing unforgiving constraints on economic productivity and growth for tomorrow.

As we have already seen, it is Russia’s death crisis that accounts for the entirety of the country’s population decline over the past decade and a half. The upsurge of illness and mortality, furthermore, has been disproportionately concentrated among men and women of working age—meaning that Russia’s labor force has been shrinking more rapidly than the population overall.

Health is a critical and central element in the complex quantity that economists have termed “human capital.” In the contemporary international economy, one additional year of life expectancy at birth is associated with an increase in per capita output of about 8 percent. A decade of lost life expectancy improvement would correspond to the loss of a doubling of per capita income. By this standard, Russia’s economic as well as its demographic future is in jeopardy.

It is not obvious that Russia will be able to recover rapidly from its health katastroika. There is an enormous amount of “negative health momentum” in the Russian situation today: with younger brothers facing worse survival prospects than older brothers, older brothers facing worse survival prospects than their fathers, and so on. Severely foreshortened adult life spans can shift the cost-benefit calculus for investments in training and higher education dramatically. On today’s mortality patterns, a Swiss man at 20 has about an 87 percent chance of making it to a notional retirement age of 65. His Russian counterpart at age 20 has less than even odds of reaching 65. Harsh excess mortality levels impose real and powerful disincentives for the mass acquisition of the technical skills that are a key to wealth generation in the modern world. Thus Russia’s health crisis may be even more generally subversive of human capital, and more powerfully corrosive of human resources, than might appear to be the case at first glance.

A consortium headed by the World Health Organization estimated that for 2005 a woman’s risk of death in childbirth in Russia was over six times higher than in Germany or Switzerland. Moreover, mortality levels for women in their twenties (the decade in which childbearing is concentrated in contemporary Russia) have been rising, not falling, in recent decades.

But Russia’s low fertility patterns are not due to any extraordinary inability of Russian women to conceive, but rather to the strong and growing tendency among childbearing women to have no more than two children—and perhaps increasingly not more than one. The new evident limits on family size in Russia, in turn, suggest a sea change in the country’s norms concerning family formation.

In 1980, fewer than one Russian newborn in nine was reportedly born out of wedlock. By 2005, the country’s illegitimacy ratio was approaching 30 percent—almost a tripling in just twenty years. Marriage is not only less common in Russia today than in the recent past; it is also markedly less stable. In 2005, the total number of marriages celebrated in Russia was down by nearly one-fourth from 1980 (a fairly typical Brezhnev-period year for marriages). On the other hand, the total number of divorces recognized in Russia has been on an erratic rise over the past generation, from under 400 divorces per 1,000 marriages in 1980 to a peak of over 800 in 2002.

In 1990, the end of the Gorbachev era, marriage was still the norm, and while divorce was very common, a distinct majority of Russian Federation women (60 percent) could expect to have entered into a first marriage and still remain in that marriage by age 50. A few years later, in 1996, the picture was already radically different: barely a third of Russia’s women (34 percent) were getting married and staying in that same marriage until age 50.

Since the end of the Soviet era, young women in Russia are opting for cohabitation before and, to a striking extent, instead of marriage. In the early 1980s, about 15 percent of women had been in consensual unions by age 25; twenty years later, the proportion was 45 percent. Many fewer of those once-cohabiting young women, moreover, seem to be moving into marital unions nowadays. Whereas roughly a generation earlier, fully half of cohabiters were married within a year, today less than a third are.

Is Russia’s post-Communist plunge in births the consequence of a “demographic shock,” or the result of what some Russian experts call a “quiet revolution” in patterns of family formation? At the moment, it is possible to see elements of both in the Russian Federation’s unfolding fertility trends. Demographic shocks tend by nature to be transient; demographic transitions or “revolutions,” considerably less so. But this much is clear: to date, no European society that has embarked upon the same demographic transition as Russia’s—declining marriage rates with rising divorce; the spread of cohabitation as alternative to marriage; delayed age at marriage and sub-replacement fertility regimens—has reverted to more “traditional” family patterns and higher levels of completed family size. There is no reason to think that in Russia it will be any different.

There are many ramifications of the dramatic decline in population in Russia, but three in particular bear heavily on the country’s prospective development and national security.

First, when Western European nations reached the level of 30 percent illegitimate births that Russia has now attained, their levels of per capita output were all dramatically higher—three times higher in France, Austria, and Britain, and higher than that in countries such as Germany, Ireland, and the Netherlands.

This means that Russia’s mothers and their children will be afforded far fewer of the social protections that their counterparts could count on in Western Europe’s more generous welfare states.

A second and related point pertains to “investment” in children. According to prevailing tenets of Western economic thought, a decline in fertility—to the extent that it occurs under conditions of orderly progress, and as a consequence of parental volition—should mean a better material environment for newborns and children because a shift to smaller desired family size, all else being equal, signifies an increase in parents’ expected commitments to each child’s education, nutrition, health care, and the like.

Yet in post-Communist Russia, there are unambiguous indications of a worsening of social well-being for a significant proportion of the country’s children—in effect, a disinvestment in children in the face of a pronounced downward shift in national fertility patterns.

School enrollment is sharply lower for primary-school-age children—99 percent in 1991 versus 91 percent in 2004. And the number of abandoned children is sharply higher. According to official statistics, as of 2004 over 400,000 Russian children below 18 years of age were in “residential care.” This means that roughly 1 child in 70 was in a children’s home, orphanage, or state boarding school. Russia is also home to a large and possibly growing contingent of street children whose numbers could well exceed those under institutional care. According to Human Rights Watch, over 100,000 children in Russia have been abandoned by their parents each year since 1996. If accurate, this number, compared to the annual tally of births for the Russian Federation, which averaged about 1.4 million a year for the 1996–2007 period, would suggest that in excess of 7 percent of Russia’s children are being discarded by their parents in this new era of steep sub-replacement fertility.

A third implication of the past decade and a half of sharply lower birth levels in Russia will be a drop-off in the country’s working-age population, and an acceleration of the tempo of population aging in the period immediately ahead. Barring only a steady and massive in-migration, Russia’s potential labor pool will shrink markedly over the coming decade and a half and continue to diminish thereafter.

In addition to its daunting fertility decline, Russia’s public health losses today are of a scale akin to what might be expected from a devastating war. Since the end of the Communist era, in fact, “excess mortality” has cost Russia hundreds of thousands of lives every year.

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed an increase in mortality rates for key elements of the Soviet population. But Russia’s health patterns did not correct course with the collapse of the USSR, as many experts assumed they would. In fact, in the first decade and a half of its post-Communist history the country’s health conditions actually became worse. Life expectancy in the Russian Federation is actually lower today than it was a half century ago in the late 1950s. In fact, the country has pioneered a unique new profile of mass debilitation and foreshortened life previously unknown in all of human history.

Like the urbanized and literate societies in Western Europe, North America, and elsewhere, the overwhelming majority of deaths in Russia today accrue from chronic rather than infectious diseases: heart disease, cancers, strokes, and the like. But in the rest of the developed world, death rates from these chronic diseases are low, relatively stable, and declining regularly over time. In the Russian Federation, by contrast, overall mortality levels are high, manifestly unstable, and rising.

The single clearest and most comprehensible summary measure of a population’s mortality prospects is its estimated expectation of life at birth. Russia’s trends in the late 1950s and early 1960s were rising briskly. In the five years between 1959 and 1964, for instance, life expectancy increased by more than two years. But then, inexplicably, overall health progress in Russia came to a sudden and spectacular halt. Over that 18-year period that roughly coincides with the Brezhnev era, Russia’s life expectancy not only stagnated, but actually fell by about a year and a half.

These losses were recovered during the Gorbachev period, but even at its pinnacle in 1986 and 1987, overall life expectancy for Russia was only marginally higher than it had been in 1964, never actually managing to cross the symbolic 70-year threshold. With the end of Communism, moreover, life expectancy went into erratic decline, plummeting a frightful four years between 1992 and 1994, recovering somewhat through 1998, but then again spiraling downward. In 2006—the most recent year for which we have such data—overall Russian life expectancy at birth was over three years lower than it had been in 1964.

The situation for Russian males has been particularly woeful. In the immediate postwar era, life expectancy for men was somewhat lower than in other developed countries—but this differential might partly be attributed to the special hardships of World War II and the evils of Stalinism. By the early 1960s, the male life expectancy gap between Russia and the more developed regions narrowed somewhat—but then life expectancy for Russian men entered into a prolonged and agonizing decline, while continued improvements characterized most of the rest of the world. By 2005, male life expectancy at birth was fully fifteen years lower in the Russian Federation than in Western Europe. It was also five years below the global average for male life expectancy, and three years below the average for the less developed regions (whose levels it had exceeded, in the early 1950s, by fully two decades). Put another way, male life expectancy in 2006 was about two and a half years lower under Putin than it had been in 1959, under Khrushchev.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau International Data Base for 2007, Russia ranked 164 out of 226 globally in overall life expectancy. Russia is below Bolivia, South America’s poorest (and least healthy) country and lower than Iraq and India, but somewhat higher than Pakistan. For females, the Russian Federation life expectancy will not be as high as in Nicaragua, Morocco, or Egypt. For males, it will be in the same league as that of Cambodia, Ghana, and Eritrea.

In the face of today’s exceptionally elevated mortality levels for Russia’s young adults, it is no wonder that an unspecified proportion of the country’s would-be mothers and fathers respond by opting for fewer offspring than they would otherwise desire. To a degree not generally appreciated, Russia’s current fertility crisis is a consequence of its mortality crisis.

How did Russia’s mortality level, which was nearly 38 percent higher than Western Europe’s in 1980, skyrocket to an astonishing 135 percent higher in 2006? What role did communicable and infectious disease play in this fateful health regression and mortality deterioration?

By any reading, the situation in Russia today sounds awful. The Russian Federation is afflicted with a serious HIV/AIDS epidemic; according to UNAIDS, as of 2008 somewhere around 1 million Russians were living with the virus. (Russia’s HIV nexus appears to be closely associated with a burgeoning phenomenon of local drug use, with sex trafficking and other forms of prostitution or “commercial sex,” and with other practices and mores relating to extramarital sex.) Russia also faces a related and evidently growing burden of tuberculosis. As of 2008, according to World Health Organization estimates, Russia was experiencing about 150,000 new TB infections a year. To make matters worse, almost half of Russia’s treated tubercular cases over the past decade have been the variant known as extreme drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB).

Yet, dismaying as these statistics are, the picture looks even worse when we consider cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality trends.

By the late 1960s, the epidemic upsurge of CVD mortality in Western industrial societies that immediately followed World War II had peaked. From the mid-1970s onward, age-standardized death rates from diseases of the circulatory system steadily declined in Western Europe. In Russia, by stark contrast, CVD mortality in 1980 was well over 50 percent higher than it had been in “old” EU states as of 1970, and the Russian population may well have been suffering the very highest incidence of mortality from diseases of the circulatory system that had ever been visited on a national population in the entire course of human history.

Over the subsequent decades, unfortunately, the level of CVD mortality in the Russian Federation veered even further upward. By 2006, Russia’s CVD mortality rate, standardizing for population structure, was an almost unbelievable 3.8 times higher than the population-weighted level reported for Western Europe.

Scarcely less alarming was Russia’s mortality rate from “external causes”—non-communicable deaths from injuries of various origins. The tale here is broadly similar to the story of CVD: impossibly high levels of death in a society that otherwise does not exhibit signs of backwardness.

In Western Europe, age-standardized mortality from injury and poisoning, as tabulated by the World Health Organization, fell by almost half between 1970 and 2006. In Russia, on the other hand, deaths from injuries and poisoning, which had been 2.5 times higher than in Western Europe in 1980, were up to 5.3 times higher as of 2006.

A broadly negative relationship was evident between mortality from injuries and per capita income. In other Western countries in 2002, an increase of 10 percent in per capita GDP was associated with a drop of about 2 points in injury deaths per 100,000 population. Yet Russia’s toll of deaths is nearly three times higher than would be predicted by its GDP. No literate and urban society in the modern world faces a risk of deaths from injuries comparable to the one that Russia experiences.

Russia’s patterns of death from injury and violence (by whatever provenance) are so extreme and brutal that they invite comparison only with the most tormented spots on the face of the planet today. The five places estimated to be roughly in the same league as Russia as of 2002 were Angola, Burundi, Congo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. To go by its level of mortality injury alone, Russia looks not like an emerging middle-income market economy at peace, but rather like an impoverished sub-Saharan conflict or post-conflict society.

Taken together, then, deaths from cardiovascular disease and from injuries and poisoning have evidently been the main drivers of modern Russia’s strange upsurge in premature mortality and its broad, prolonged retrogression in public health conditions. One final factor that is intimately associated with both of these causes of mortality is alcohol abuse.

Unlike drinking patterns prevalent in, say, Mediterranean regions—where wine is regarded as an elixir for enhancing conversation over meals and other social gatherings, and where public drunkenness carries an embarrassing stigma—mind-numbing, stupefying binge drinking of hard spirits is an accepted norm in Russia and greatly increases the danger of fatal injury through falls, traffic accidents, violent confrontations, homicide, suicide, and so on. Further, extreme binge drinking (especially of hard spirits) is associated with stress on the cardiovascular system and heightened risk of CVD mortality.

How many Russians are actually drinkers, and how heavily do they actually drink? Officially, Russia classifies some 7 million out of roughly 120 million persons over 15 years of age, or roughly 6 percent of its adult population, as heavy drinkers. But the numbers are surely higher than this. According to data compiled by the World Health Organization, as of 2003 Russia was Europe’s heaviest per capita spirits consumer; its reported hard liquor consumption was over four times as high as Portugal’s, three times that of Germany or Spain, and over two and a half times higher than that of France.

Yet even these numbers may substantially understate hard spirit use in Russia, since the WHO figures follow only the retail sale of hard liquor. But samogon—home-brew, or “moonshine”—is, according to some Russian researchers, a huge component of the country’s overall intake. Professor Alexander Nemstov, perhaps Russia’s leading specialist in this area, argues that Russia’s adult population—women as well as men—puts down the equivalent of a bottle of vodka per week.

From the epidemiological standpoint, local-level studies have offered fairly chilling proof that alcohol is a direct factor in premature mortality. One forensic investigation of blood alcohol content by a medical examiner’s office in a city in the Urals, for example, indicated that over 40 percent of the younger male decedents evaluated had probably been alcohol-impaired or severely intoxicated at the time of death—including one quarter of the deaths from heart disease and over half of those from accidents or injuries. But medical and epidemiological studies have also demonstrated that, in addition to its many deaths from consumption of ordinary alcohol, Russia also suffers a grisly toll from alcohol poisoning, as the country’s drinkers, in their desperate quest for intoxication, down not only sometimes severely impure samogon, but also perfumes, alcohol-based medicines, cleaning solutions, and other deadly liquids. Death rates from such alcohol poisoning appear to be at least one hundred times higher in Russia than the United States—this despite the fact that the retail price in Russia today is lower for a liter of vodka than a liter of milk.

Josef Stalin is said to have coldly joked that one death was a tragedy, while one million deaths was just a statistic. This comment seems to apply to post-Communist Russia as well to Stalin’s own deranged regime. For the better part of a generation, Russia has suffered something akin to wartime population losses during year after year of peacetime political order. In the United Nations Development Program’s annually tabulated “Human Development Index,” which uses health as well as economic data to measure a country’s living standards as they affect quality of life, Russia was number 73 out of 179. A country of virtually universal literacy and quite respectable general educational attainment, with a scientific cadre that mastered nuclear fission over half a century ago and launches orbital spacecraft and interplanetary probes today, finds itself ranked on this metric between Mauritius and Ecuador.

In the modern era, population decline itself need not be a cause for acute economic alarm. Italy, Germany, and Japan are among the societies where signs of incipient population decline are being registered nowadays: all of these are affluent countries, and all can anticipate continuing improvements in their respective levels of prosperity (albeit at a slower tempo than some might prefer). Depopulation with Russian characteristics—population decline powered by an explosive upsurge of illness and mortality—is altogether more forbidding in its economic implications, not only forcing down popular well-being today, but also placing unforgiving constraints on economic productivity and growth for tomorrow.

As we have already seen, it is Russia’s death crisis that accounts for the entirety of the country’s population decline over the past decade and a half. The upsurge of illness and mortality, furthermore, has been disproportionately concentrated among men and women of working age—meaning that Russia’s labor force has been shrinking more rapidly than the population overall.

Health is a critical and central element in the complex quantity that economists have termed “human capital.” In the contemporary international economy, one additional year of life expectancy at birth is associated with an increase in per capita output of about 8 percent. A decade of lost life expectancy improvement would correspond to the loss of a doubling of per capita income. By this standard, Russia’s economic as well as its demographic future is in jeopardy.

It is not obvious that Russia will be able to recover rapidly from its health katastroika. There is an enormous amount of “negative health momentum” in the Russian situation today: with younger brothers facing worse survival prospects than older brothers, older brothers facing worse survival prospects than their fathers, and so on. Severely foreshortened adult life spans can shift the cost-benefit calculus for investments in training and higher education dramatically. On today’s mortality patterns, a Swiss man at 20 has about an 87 percent chance of making it to a notional retirement age of 65. His Russian counterpart at age 20 has less than even odds of reaching 65. Harsh excess mortality levels impose real and powerful disincentives for the mass acquisition of the technical skills that are a key to wealth generation in the modern world. Thus Russia’s health crisis may be even more generally subversive of human capital, and more powerfully corrosive of human resources, than might appear to be the case at first glance.

Adopted teen returns to Russia...

In Russia, teen complains of adoptive US parents

Mar 26,`13 -- A teenager adopted by an American couple has returned to Russia, claiming that his adoptive family treated him badly and that he lived on the streets of Philadelphia and stole just to survive, Russian state media reported.

In Russia, teen complains of adoptive US parents

Mar 26,`13 -- A teenager adopted by an American couple has returned to Russia, claiming that his adoptive family treated him badly and that he lived on the streets of Philadelphia and stole just to survive, Russian state media reported.

The allegations by Alexander Abnosov, who was adopted around five years ago and is now 18, will likely fuel outrage here over the fate of Russian children adopted by Americans. It's an anger that the Kremlin has carefully stoked in recent months to justify its controversial ban on U.S. adoptions. Russia's Channel 1 and Rossiya television - which are both state controlled - reported Tuesday that Abnosov returned from a Philadelphia suburb to the Volga river city of Cheboksary, where his 72-year-old grandmother lives. Russian media identified the teen as Alexander Abnosov, but also show him displaying a U.S. passport that gives his name as Joshua Alexander Salotti.

Abnosov, who spoke in a soft voice and appeared somewhat restrained, complained to Rossiya that his adoptive mother was "nagging at small things." "She would make any small problem big," he said on Channel 1. He also told Channel 1 that he fled home because of the conflicts with his adoptive mother, staying on the streets for about three months and stealing. "I was stealing stuff and sold them to get some food," he said with a shy smile.

According to the daily Komsomolskaya Pravda, Abnosov says that his parents visited him while he stayed in a shelter in Philadelphia, but that they didn't ask him to come home as he'd expected. Channel 1 said his adoptive father gave him $500 to buy a ticket to Russia, though it wasn't clear when he arrived here. The newspaper said it reached Abnosov's adoptive mother, who denied driving him away. She was quoted as saying he was asked to come home, but said he wanted to return to Russia where he has relatives to care for. The teen's adoptive parents - identified in the media reports as Steve and Jackie Salotti - could not immediately be reached Tuesday. A woman who identified herself as a relative at the couple's home in Collegeville, Pennsylvania, said the parents weren't there and did not want to discuss the case.

Abnosov's story was top news on Russian state television, which tried to cast it as an example of the alleged misfortunes that befall Russian children adopted by U.S. parents. The Russian government in December banned all American adoptions of Russian children in retaliation for a new U.S. law targeting alleged Russian human-rights violators. Some 60,000 children have been adopted by Americans in the past two decades, and many Russians disagree with the ban, seeing it as a politically driven move depriving children of a chance to have a family.

MORE

Similar threads

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 137

- Replies

- 48

- Views

- 599

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 179

Latest Discussions

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 26

- Replies

- 23

- Views

- 53

- Replies

- 145

- Views

- 640

Forum List

-

-

-

-

-

Political Satire 8037

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

ObamaCare 781

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Member Usernotes 468

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-