In fact, adjusted for education and hours worked government workers appear to be underpaid. It is especially true in the professions, such as law, accounting and finance, where people are dramatically underpaid relative to the private market. In my profession - investments - government workers are often paid 10% to 20% of what people make in similar positions in the private sector.

Are Government Employees Overpaid? Still No. Rortybomb

The governments workforce is more educated than the private workforce. For instance, the governments college plus level is 54%, while all private workforce is 35%. Some college is 14% of government workers, 19% of the private workforce. So this is important to control for.

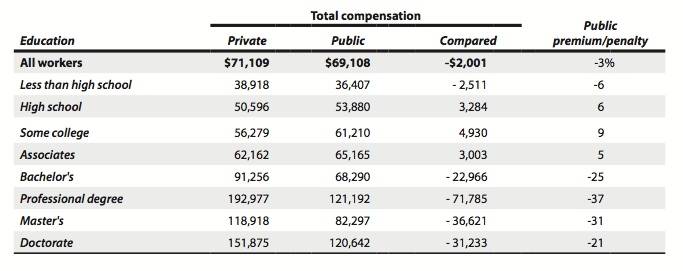

Here is the penalty government workers take when you include all benefits across both categories:

On average, government workers make 3% less total compensation when you control for education levels. As someone who once considered doing regulatory work with his professional Masters degree work, I can completely agree that theres a 30%+ pay gap between the public and private sector.

Are Government Employees Overpaid? Still No. Rortybomb