Xenophon

Gone and forgotten

President Millard Fillmore was very concerned. For years, American sailors were being killed by Japan when they were shipwrecked, and it had to stop. These sailors, taking part in the whale trade, were a vital source of wealth for young America. These men, often washed up on the shores of Japan after violent storms, could not enjoy the usual rights bestowed upon shipwrecked men, instead, Japan, isolated and xenophobic, had as a matter of state policy, killed outright all foreigners, except for a small Dutch trading mission in Nagasaki.

The President knew there were other concerns as well, for Japan offered a virgin market for US goods, as well as good harbors for American whalers and trade ships, and he very much wanted to secure these. In those days of the 1850s, diplomatic missions were more often than not carried out by active duty Naval officers, rather then Washington politicians. But who should the President send? The man selected must be of impeccable moral character, must have a through knowledge of diplomacy, as well as a commanding presence and a sense of showmanship. The Japanese were known to respond only to the strictest essence of formality, so the leader of the mission must also have patience, and since there was an excellent chance the mission might go badly, he also needed to be a skilled military officer. It seemed impossible to find such a paragon, but fortunately, the President found such a man.

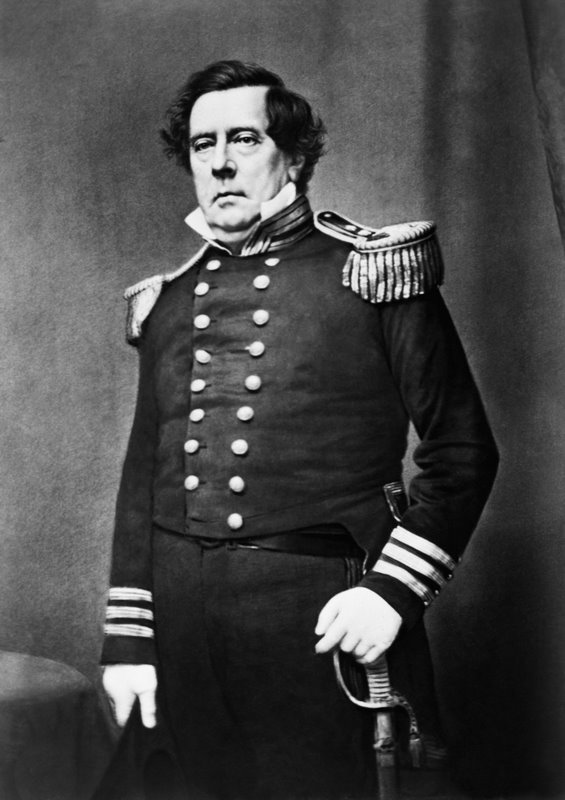

Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry was the man the President selected for this delicate, yet vital mission. The younger brother of the famed hero of Lake Erie in the war of 1812, Perry was perhaps the only man in the entire country suitable for the assignment. Known throughout the Navy as "the cast-iron Commodore" and "Old Matt", he had the right combination of astute imagination, high regaurd for tradition, and careful attention to detail.

"We will demand as a right, not solicit as a favor, those acts of courtesy due one civilized nation to another" Perry thundered.

Some of the government officials in Washington were dubious. President Fillmore prepared a special letter addressed to the Emperor of Japan. Perry would carry this in an elaborate, hand-carved box of fragrant rose-wood. And he requested the letter and other official documents be inscribed on the finest vellum, embellished with government seals and ribbons. In the box were delicate gifts for the Emperor.

Preparing this massive undertaking took two years, during which Perry read up on what was known of Japan, and also hand picked the officers of his fleet for this special duty. All the officers who would come into close contact with the Japanese would be tall, formal in manor, and distinctive in outward appearance.

Perry arrived at Yedo bay (modern Tokyo bay) on July 8, 1853, aboard his flagship, the USS Susquehanna, the most modern side-wheel steam frigate in the US Navy. With her was another big, impressive side-wheeler, the Mississippi, and two trim sloops, the Plymouth and the Saratoga. The ships steamed slowly up the bay and anchored off the town of Uraga. Suddenly, the warships were surrounded by a throng of small picket vessels, and the local Shogun warned the Americans to leave at once. Perry, unfazed, ignored the warning, knowing full well the tiny Japanese vessels could not harm the powerful American squadron. The frustrated Japanese now sent an officer alongside in a small boat and demanded to see the American commanding officer.

Perry's officers politely told this officer that "The Lord of the Forbidden Interior could not possibly demean his rank by appearing on deck to carry on a discussion".

This was the answer Perry had ordered and the crew was astonished to see that the Japanese took no affront. Instead, as Perry knew they would be, they seemed duly impressed. "We have the vice-governor of Uraga aboard", said the Japanese officer, "he is of very high rank."

"Why did you not bring the governor?" he was asked by the petty officer who was carrying on the liaison.

"He is forbidden to be on ships", came the answer. And would the Lord of the Forbidden Interior designate an officer whose rank was appropriate to conversing with the vice-governor?

Here is were the long months of selection and training were to prove themselves. Perry now sent, not a Captain or a Commander, but a junior Lieutenant. The lieutenant after a ceremonious greeting, announced that the expedition was a most honored one, for it bore a message from the President of the United States to the Emperor himself. Could the vice-governor see this message? No one was permitted to see it but the Emperor or one of his princes. However, if the governor himself would appear, he would be shown a copy of the letter.

A day later, after the vice-governor had retired to shore for a conference, the governor sailed out on an elaborately decorated barge. Now Perry, who had remained completely out of site at all times, sent Captain Buchanan of his flagship to carry on the ceremonious negotiations at this level. The governor was impressed when he saw the rosewood box. Yet he hesitated. He was not certain that he would be best be serving his Emperor by permitting foreigners to land to meet with members of the royal household.

"That would indeed be too bad", he was told, "for the Lord of the Forbidden Interior is committed to delivering the message, or dying in the attempt."

The governor carefully eyed the tremendous guns of the ships, which had been purposely readied and exposed. Then, displaying no sign of emotion, he politely requested time to consult with the proper authorities, and returned to shore.

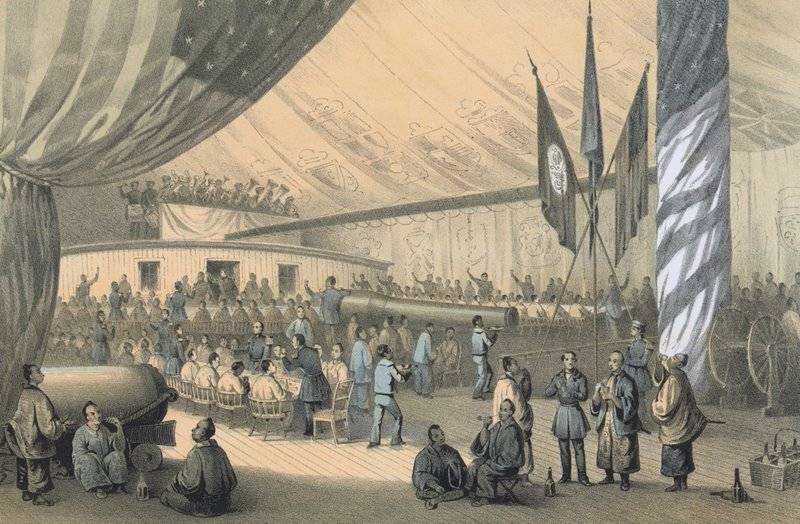

It was not until July 14 that Perry permitted himself to be seen. The Japanese had set up a fine pavilion on the shore, to which would come the Price of Idzu, the properly ranked representative of the Emperor. The ships had all moved closer to shore, where the Japanese could easily see that his mission of peace was well supported by the necessary engines of war. One hundred Marines in well-starched dress uniforms had gone ashore and were lined up in procession with a company of seamen and two navy bands.

At the proper moment, Perry appeared on the spotless deck of the Susquehanna in full dress, and was helped into his official barge to the sound of a thirteen-gun salute which echoed across the bay. Then, proceeded by fifteen boats, each mounting a gun, the barge advanced at a dignified pace to the shore. The extent to which Perry had prepared and supervised each detail was now seen at its best. As he stepped ashore, he was flanked by two superb looking black seamen, the tallest, most impressive men he could find in the navy. And in front of them marched two midshipmen, bearing the rosewood box. To the Japanese, this pomp and pageantry signified that America was a nation worthy to carry on trade with Japan.

The meeting of Prince Idzu and the Commodore was not, however, the end of the negotiations. Perry was well aware that he could by no means expect an official answer to the request in the letter that trade be opened within a few days, or even weeks. "I shall return for an answer within six months," stated perry solemnly.

In the United States, some newspapers severely criticized the Commodore, and suggested that the government attend to serious matters and discourage this type of 'humbug." In February 1854, The American squadron returned. Further ceremonies took place. There were exchanges of gifts: for the Americans, silks and carvings and other Japanese handicrafts; for the Japanese, firearms, tools, clocks, and the most unusual item of all-a miniature railway with an engine which had a speed of twenty miles per hour.

Then the results of all this "humbug" were made clear. The Japanese, impressed with Perry's stratagem, and fully aware now of American naval strength, announced that they would sign the treaty. And thus it was that an inspired officer won the most important peacetime battle of the nineteenth century for the US Navy.

The President knew there were other concerns as well, for Japan offered a virgin market for US goods, as well as good harbors for American whalers and trade ships, and he very much wanted to secure these. In those days of the 1850s, diplomatic missions were more often than not carried out by active duty Naval officers, rather then Washington politicians. But who should the President send? The man selected must be of impeccable moral character, must have a through knowledge of diplomacy, as well as a commanding presence and a sense of showmanship. The Japanese were known to respond only to the strictest essence of formality, so the leader of the mission must also have patience, and since there was an excellent chance the mission might go badly, he also needed to be a skilled military officer. It seemed impossible to find such a paragon, but fortunately, the President found such a man.

Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry was the man the President selected for this delicate, yet vital mission. The younger brother of the famed hero of Lake Erie in the war of 1812, Perry was perhaps the only man in the entire country suitable for the assignment. Known throughout the Navy as "the cast-iron Commodore" and "Old Matt", he had the right combination of astute imagination, high regaurd for tradition, and careful attention to detail.

"We will demand as a right, not solicit as a favor, those acts of courtesy due one civilized nation to another" Perry thundered.

Some of the government officials in Washington were dubious. President Fillmore prepared a special letter addressed to the Emperor of Japan. Perry would carry this in an elaborate, hand-carved box of fragrant rose-wood. And he requested the letter and other official documents be inscribed on the finest vellum, embellished with government seals and ribbons. In the box were delicate gifts for the Emperor.

Preparing this massive undertaking took two years, during which Perry read up on what was known of Japan, and also hand picked the officers of his fleet for this special duty. All the officers who would come into close contact with the Japanese would be tall, formal in manor, and distinctive in outward appearance.

Perry arrived at Yedo bay (modern Tokyo bay) on July 8, 1853, aboard his flagship, the USS Susquehanna, the most modern side-wheel steam frigate in the US Navy. With her was another big, impressive side-wheeler, the Mississippi, and two trim sloops, the Plymouth and the Saratoga. The ships steamed slowly up the bay and anchored off the town of Uraga. Suddenly, the warships were surrounded by a throng of small picket vessels, and the local Shogun warned the Americans to leave at once. Perry, unfazed, ignored the warning, knowing full well the tiny Japanese vessels could not harm the powerful American squadron. The frustrated Japanese now sent an officer alongside in a small boat and demanded to see the American commanding officer.

Perry's officers politely told this officer that "The Lord of the Forbidden Interior could not possibly demean his rank by appearing on deck to carry on a discussion".

This was the answer Perry had ordered and the crew was astonished to see that the Japanese took no affront. Instead, as Perry knew they would be, they seemed duly impressed. "We have the vice-governor of Uraga aboard", said the Japanese officer, "he is of very high rank."

"Why did you not bring the governor?" he was asked by the petty officer who was carrying on the liaison.

"He is forbidden to be on ships", came the answer. And would the Lord of the Forbidden Interior designate an officer whose rank was appropriate to conversing with the vice-governor?

Here is were the long months of selection and training were to prove themselves. Perry now sent, not a Captain or a Commander, but a junior Lieutenant. The lieutenant after a ceremonious greeting, announced that the expedition was a most honored one, for it bore a message from the President of the United States to the Emperor himself. Could the vice-governor see this message? No one was permitted to see it but the Emperor or one of his princes. However, if the governor himself would appear, he would be shown a copy of the letter.

A day later, after the vice-governor had retired to shore for a conference, the governor sailed out on an elaborately decorated barge. Now Perry, who had remained completely out of site at all times, sent Captain Buchanan of his flagship to carry on the ceremonious negotiations at this level. The governor was impressed when he saw the rosewood box. Yet he hesitated. He was not certain that he would be best be serving his Emperor by permitting foreigners to land to meet with members of the royal household.

"That would indeed be too bad", he was told, "for the Lord of the Forbidden Interior is committed to delivering the message, or dying in the attempt."

The governor carefully eyed the tremendous guns of the ships, which had been purposely readied and exposed. Then, displaying no sign of emotion, he politely requested time to consult with the proper authorities, and returned to shore.

It was not until July 14 that Perry permitted himself to be seen. The Japanese had set up a fine pavilion on the shore, to which would come the Price of Idzu, the properly ranked representative of the Emperor. The ships had all moved closer to shore, where the Japanese could easily see that his mission of peace was well supported by the necessary engines of war. One hundred Marines in well-starched dress uniforms had gone ashore and were lined up in procession with a company of seamen and two navy bands.

At the proper moment, Perry appeared on the spotless deck of the Susquehanna in full dress, and was helped into his official barge to the sound of a thirteen-gun salute which echoed across the bay. Then, proceeded by fifteen boats, each mounting a gun, the barge advanced at a dignified pace to the shore. The extent to which Perry had prepared and supervised each detail was now seen at its best. As he stepped ashore, he was flanked by two superb looking black seamen, the tallest, most impressive men he could find in the navy. And in front of them marched two midshipmen, bearing the rosewood box. To the Japanese, this pomp and pageantry signified that America was a nation worthy to carry on trade with Japan.

The meeting of Prince Idzu and the Commodore was not, however, the end of the negotiations. Perry was well aware that he could by no means expect an official answer to the request in the letter that trade be opened within a few days, or even weeks. "I shall return for an answer within six months," stated perry solemnly.

In the United States, some newspapers severely criticized the Commodore, and suggested that the government attend to serious matters and discourage this type of 'humbug." In February 1854, The American squadron returned. Further ceremonies took place. There were exchanges of gifts: for the Americans, silks and carvings and other Japanese handicrafts; for the Japanese, firearms, tools, clocks, and the most unusual item of all-a miniature railway with an engine which had a speed of twenty miles per hour.

Then the results of all this "humbug" were made clear. The Japanese, impressed with Perry's stratagem, and fully aware now of American naval strength, announced that they would sign the treaty. And thus it was that an inspired officer won the most important peacetime battle of the nineteenth century for the US Navy.