Granny says, "Now dem zombies gonna wake up an' give ever'body the plague - we all gonna die...

'Black Death pit' unearthed by Crossrail project

14 March 2013 - Excavations for London's Crossrail project have unearthed bodies believed to date from the time of the Black Death.

'Black Death pit' unearthed by Crossrail project

14 March 2013 - Excavations for London's Crossrail project have unearthed bodies believed to date from the time of the Black Death.

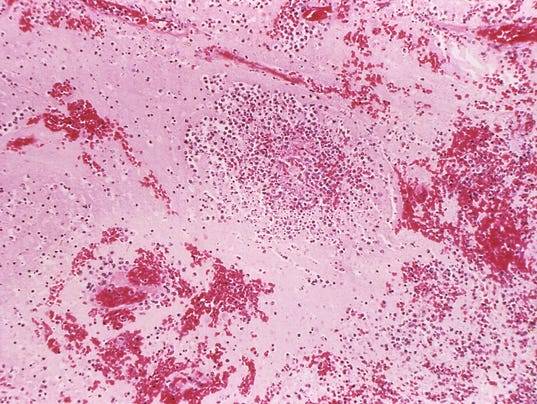

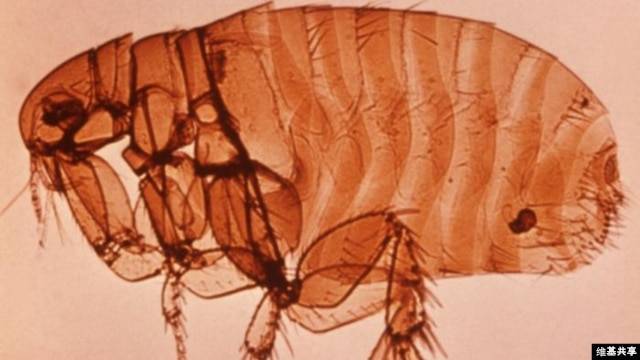

A burial ground was known to be in an area outside the City of London, but its exact location remained a mystery. Thirteen bodies have been found so far in the 5.5m-wide shaft at the edge of Charterhouse Square, alongside pottery dated to the mid-14th Century. Analysis will shed light on the plague and the Londoners of the day. DNA taken from the skeletons may also help chart the development and spread of the bacterium that caused the plague that became known as the Black Death. Charterhouse Square lies in an area that was once outside the walls of London, referred to at the time as "No-man's Land".

The skeletons' arrangement in two neat rows suggests they date from the earliest era of the Black Death, before it fully developed into the pandemic that in later years saw bodies dumped haphazardly into mass graves. Archaeologists working for Crossrail and the Museum of London will continue to dig in a bid to discover further remains, or any finds from earlier eras. The £14.8bn Crossrail project aims to establish a 118km-long (73-mile) high-speed rail link with 37 stations across London, and is due to open in 2018. Because of the project's underground scope, significant research was undertaken into the archaeology likely to be found during the course of the construction.

Taken together, the project's 40 sites comprise one of the UK's largest archaeological ventures. Teams have already discovered skeletons near Liverpool Street, a Bronze-Age transport route, and an array of other finds, including the largest piece of amber ever found in the UK. "We've found archaeology from pretty much all periods - from the very ancient prehistoric right up to a 20th-Century industrial site, but this site is probably the most important medieval site we've got," said Jay Carver, project archaeologist for Crossrail. "This is one of the most significant discoveries - quite small in extent but highly significant because of its data and what is represented in the shaft," he told BBC News.

The find is providing more than just a precise location for the long-lost burial ground, said Nick Elsden, project manager from the Museum of London Archaeology, which is working with Crossrail on its sites. "We've got a snapshot of the population from the 14th Century - we'll look for signs that they'd done a lot of heavy, hard work, which will show on the bones, and general things about their health and their physique," he added. "That tells us something about the population at the time - about them as individual people, as well as being victims of the Black Death."

More BBC News - 'Black Death pit' unearthed by Crossrail project